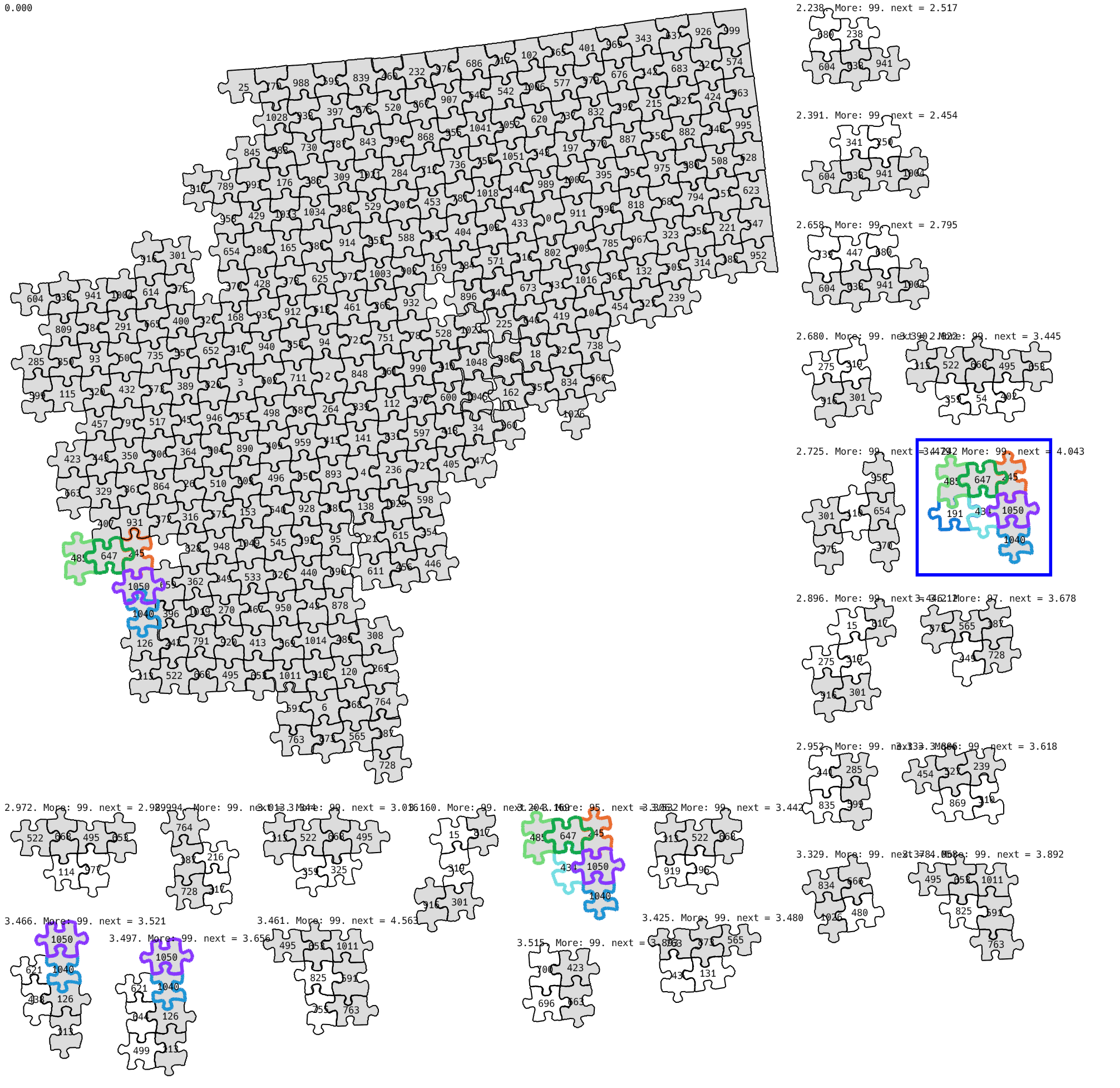

Welcome to Part 2! In the previous post we discussed how to normalize the photo, detect pieces, find good pairs, and even tried to greedily solve the whole puzzle, but didn’t succeed in the last one. This time we will talk about how to actually make it work, and try to solve a bigger 1000-piece completely white puzzle.

Make it work

Last time we tried to greedily match pairs until all pieces were added to the picture. That also included pairs, which are definitely incorrect. Let’s at least add some threshold for what could be called a good pair of pieces and not join pairs with worse scores. This will lead to several not connected parts of the puzzle, but at least it will not be complete nonsense.

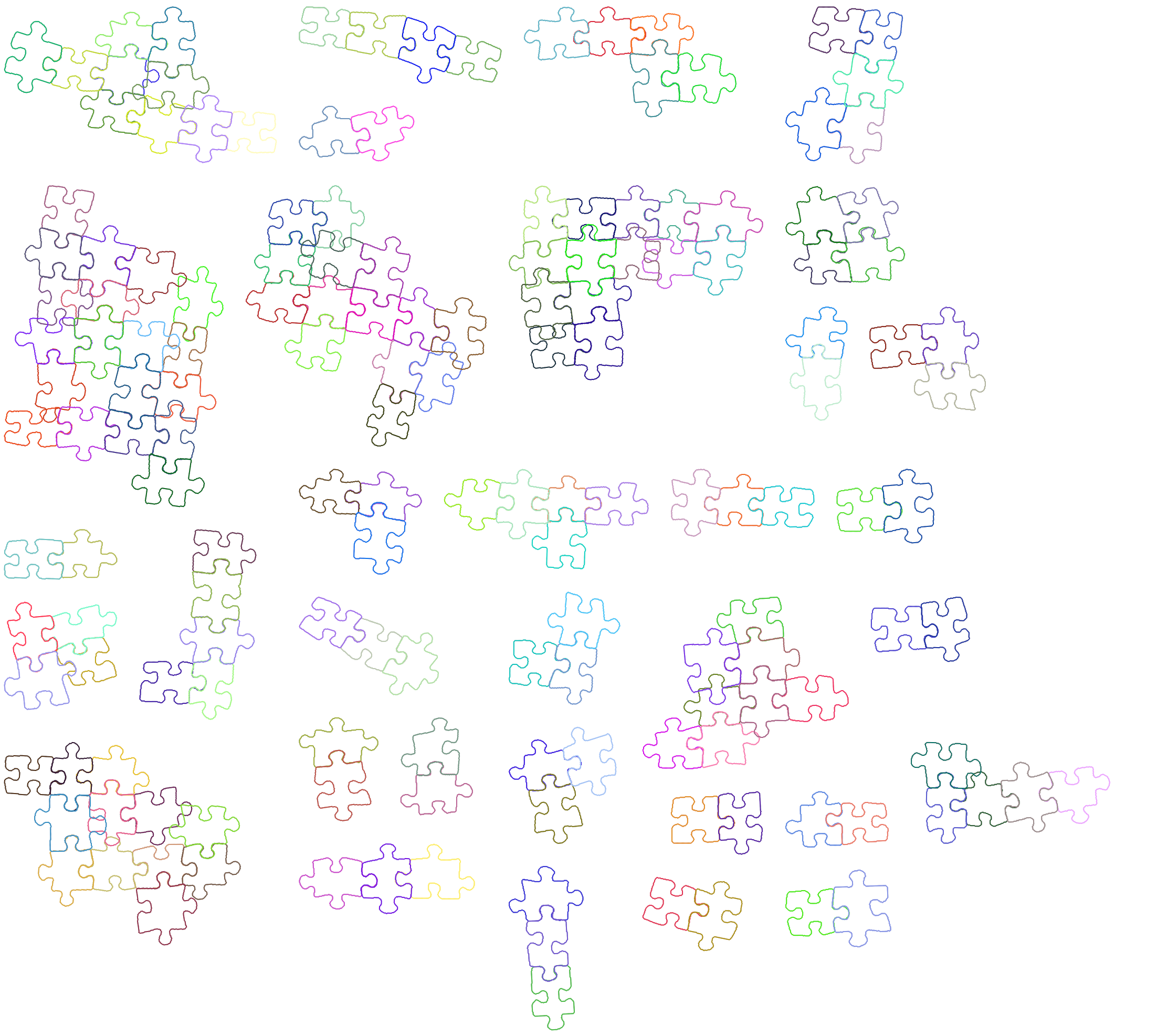

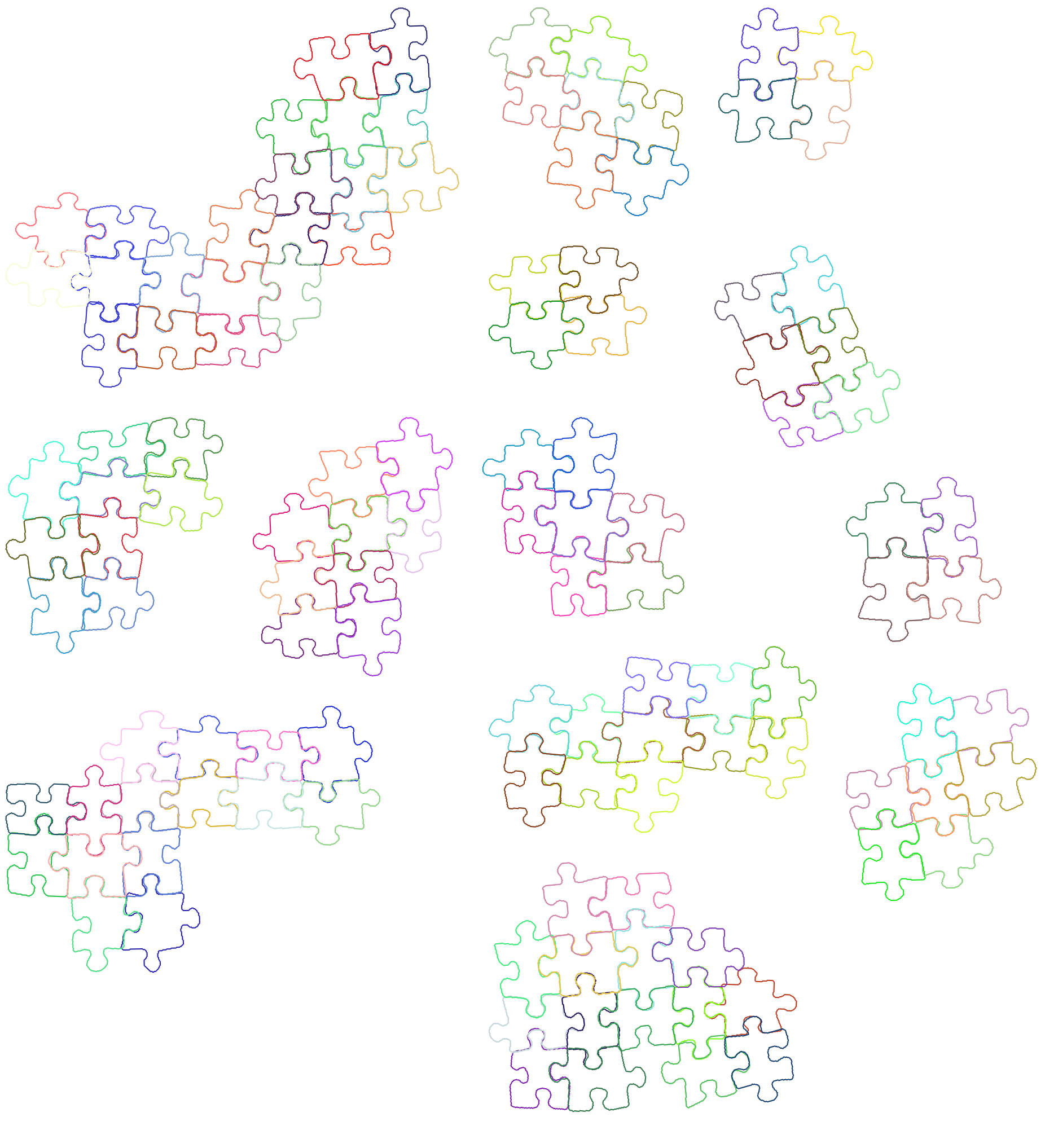

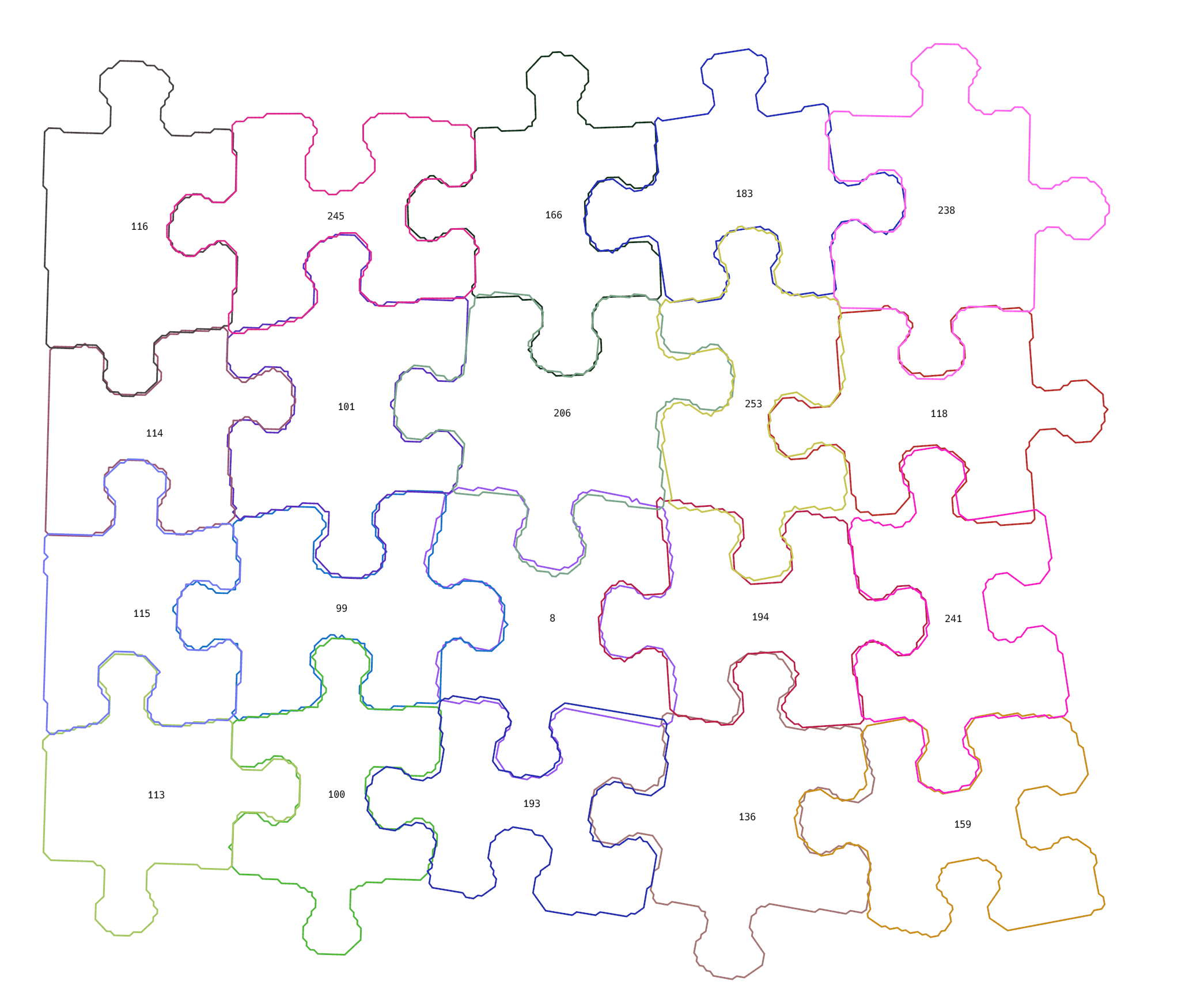

This picture looks better, but even without looking at the details, it is obvious that most parts are incorrect. There are a lot of reasons why solutions are wrong, but let’s discuss only one of them. If you look at subgraphs of size 2x2, you can see that usually, 3 edges out of 4 look reasonable, while the last one is completely off. It happened because we created such blocks based on 3 edges, and didn’t even check the 4th one, which was created automatically.

2x2

Let’s simplify the task even more, and just try to find a good 2x2 block. In this case, we can manually add a check for the last edge.

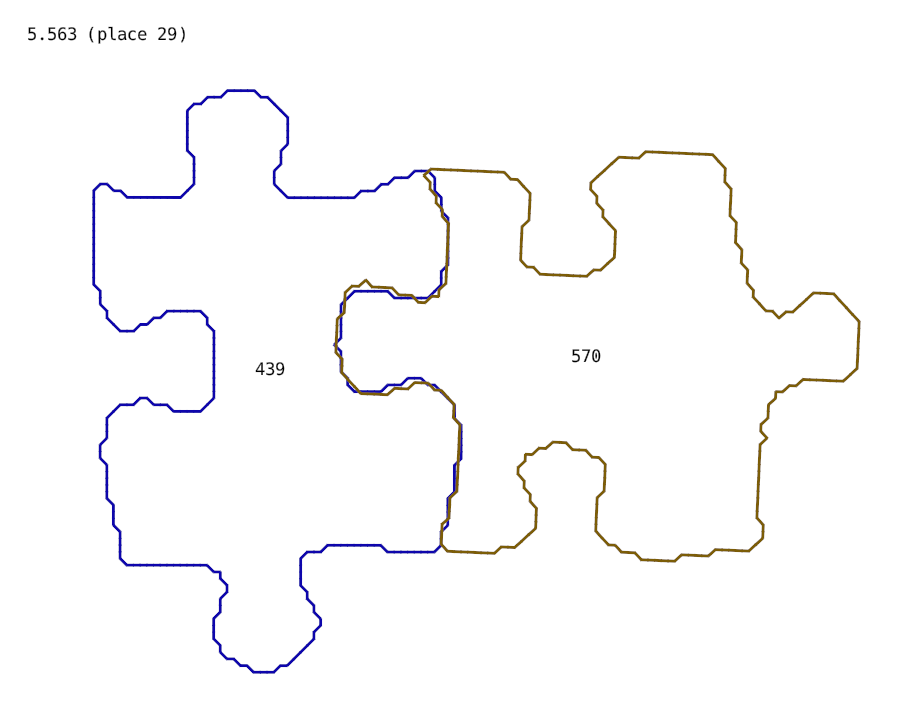

But you still can see that one out of four edges is bad? Let’s look closer at one example.

You can guess that the actual score between the top two pieces is not that bad, the problem comes from the way we put all 4 pieces together. When I calculated scores for pairs, I tried to move pieces around with local optimizations to improve the score, and then saved the best relative positions of pieces. When I wanted to put all 4 pieces on the surface, I started with the bottom left one, and put two pieces connected to it using those relative positions. And to put the top-right piece, I only used the bottom-right one.

There is a simple way to solve this problem. After generating solutions, we can run local optimizations again, now trying to minimize the total score between all 4 pieces. Now it looks much better (well, in fact, most of them are still incorrect, but at least better than before)!

If we found some fours, which look reasonable, we can try to join them together, and build bigger components.

Evolutionary algorithms

I also wrote some evolutionary algorithm to solve the problem. Let’s say we start from just two pieces connected together. There are a lot of possible pairs, but let’s just choose the top 100 of them by score and use them as our initial 100 solutions. Then for each solution, we try to add another piece in all possible ways. It generates a lot of 3-piece solutions. We can sort them by score and leave just the top 100 of them. Later we add 4th piece to all of them, and again only leave the top 100 of the solutions.

Why is this algorithm good? If we incorrectly added some pieces to the solution, we will only notice it several steps later, and it will be hard to decide which pieces need to be removed. In the case of an evolutionary algorithm, the overall score of such solutions becomes bad, and we drop them. While solutions, which didn’t use that wrong piece get a better score and stay.

But there is a tricky part of this algorithm. How to choose a score function? We can start with a simple one like an average score between all pairs of adjacent pieces. But it will lead to solutions with a small number of adjacent pieces. For example, instead of a 2x2 solution with 4 edges, it will probably choose a solution of form 1x4 with 3 edges. We can try to include the number of edges in the score function. Or we can say that the “bounding box” of the generated solution should be a small square. There are some ways to fix it, but there is no ideal solution.

Here is one example of what you can get with it:

Start from the edge

One popular technique used when solving jigsaw puzzles by hand is starting from the sides. You can easily find pieces, which should be on the border and try to connect them.

We can use the same idea in our evolutionary algorithm. Let’s just start only with pieces, which have at least one straight side.

Physical world

I should say I did all of the experiments to this point only on the computer without trying to fit pieces in the physical world. So I could only guess if the solution generated by my program is correct or not. The reason for this was very simple. When I started writing code, I only had a photo of the puzzle, which I took months ago. The actual pieces were in the box, and I didn’t have a way to understand which piece from the photo corresponded to which piece in the box.

So my plan was to make something potentially working, open the box again, take a new photo, and test. At this point I thought that at least some pairs of pieces are probably connected correctly, so I can try to fit them into the real world.

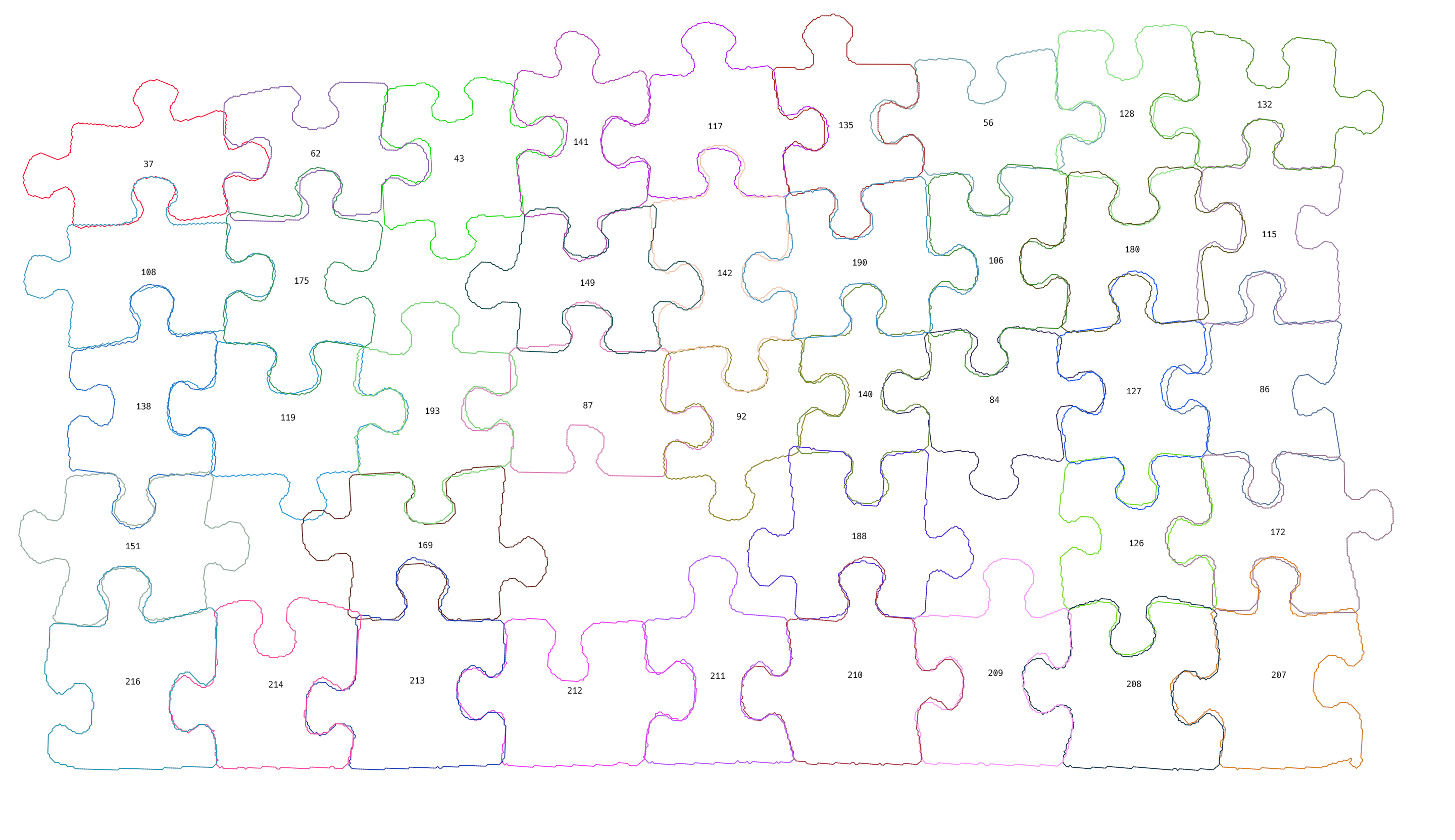

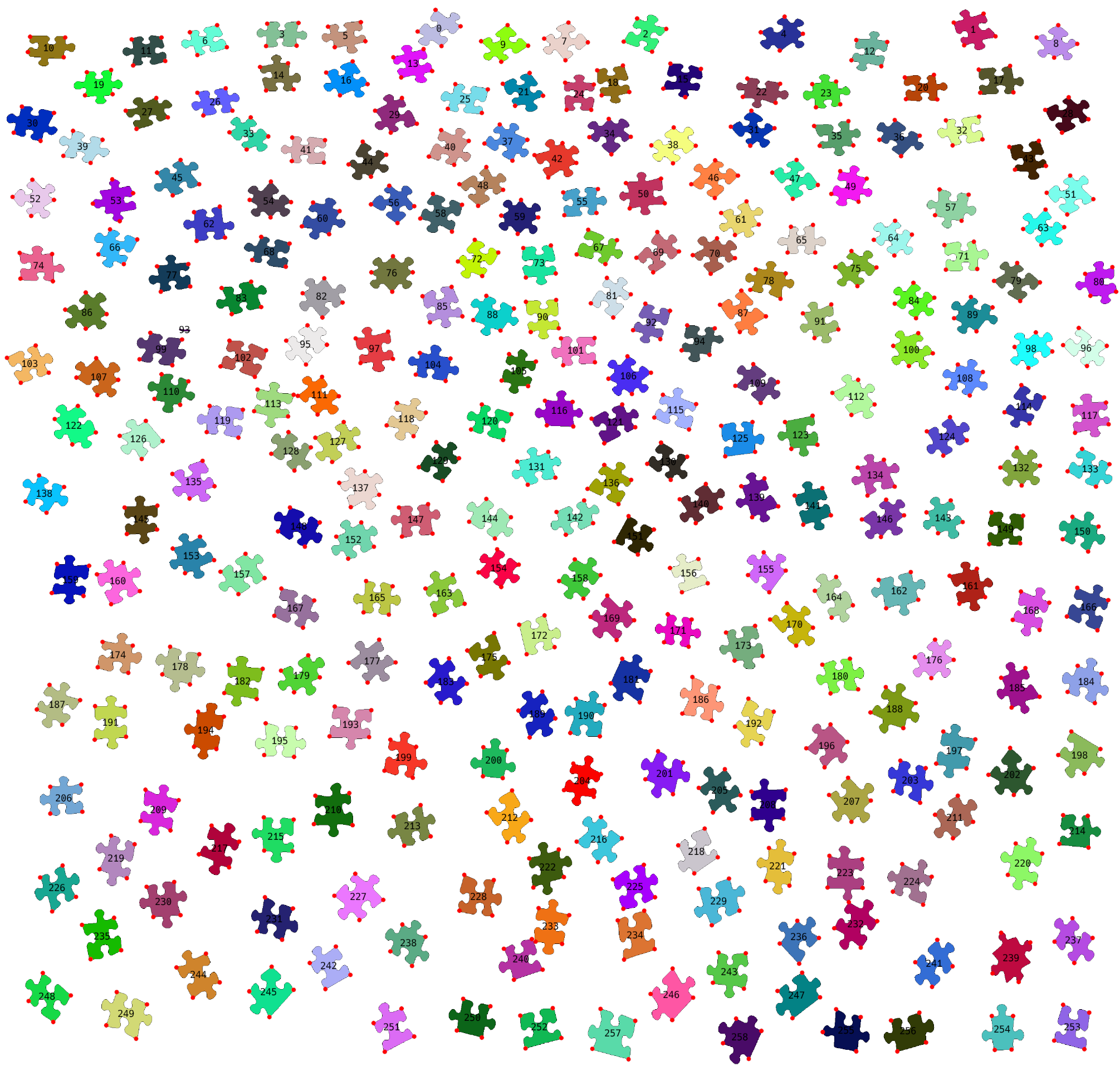

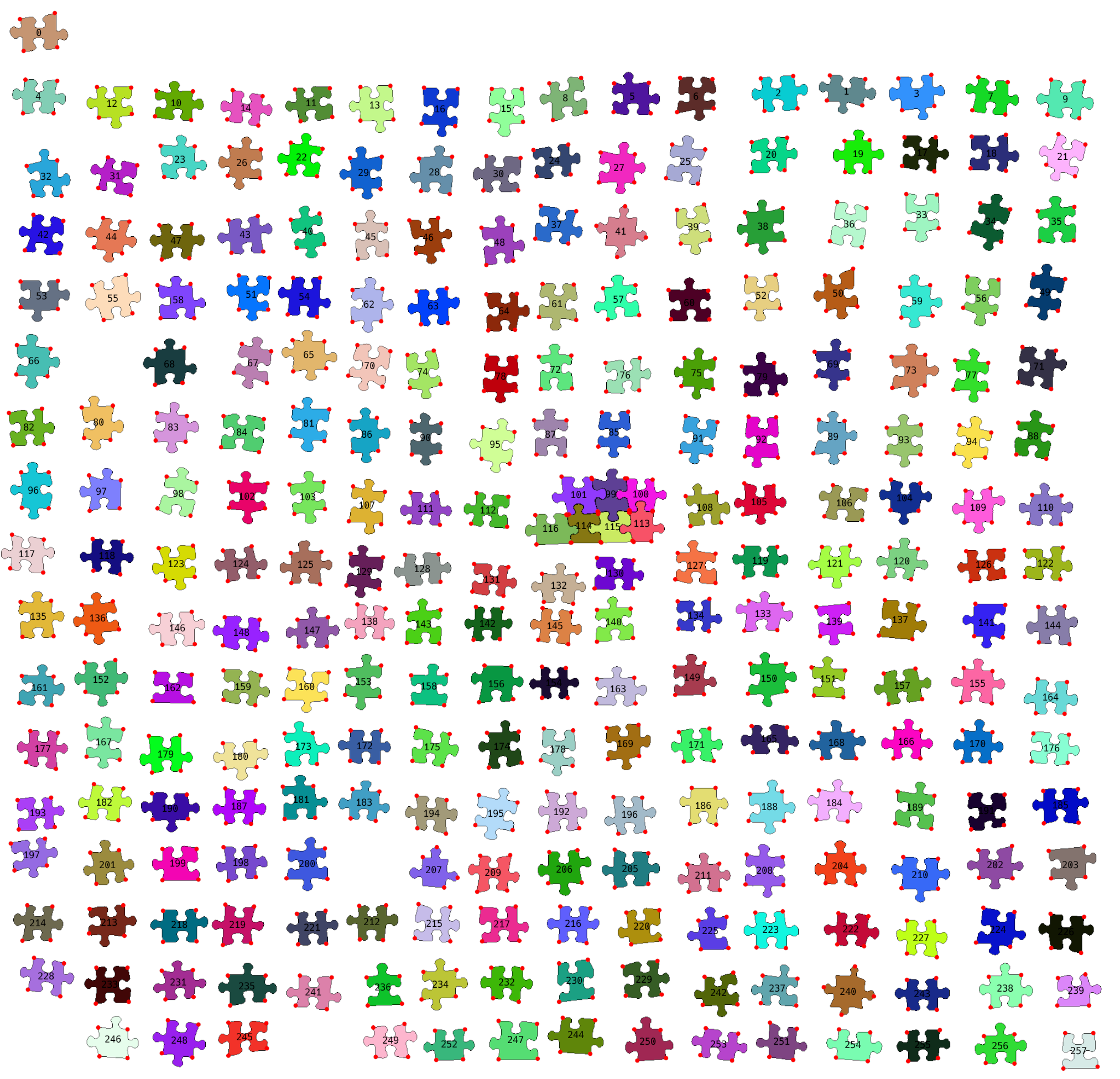

To actually be able to understand which pieces my program suggests to join, I numbered all of them:

My initial puzzle had pieces, which are not completely white, but I didn’t know how to detect such pieces properly, so I left only white pieces.

Parsed version:

The program suggested some solutions, most of the pairs didn’t work, but some of them did! Also, I realized that finding pieces by a number is quite a hard task, so I tried to put them in a more structured way. And I fixed a problem with scaling, which I mentioned in the previous post.

After fixing scaling issues suggested solutions started looking more reasonable.

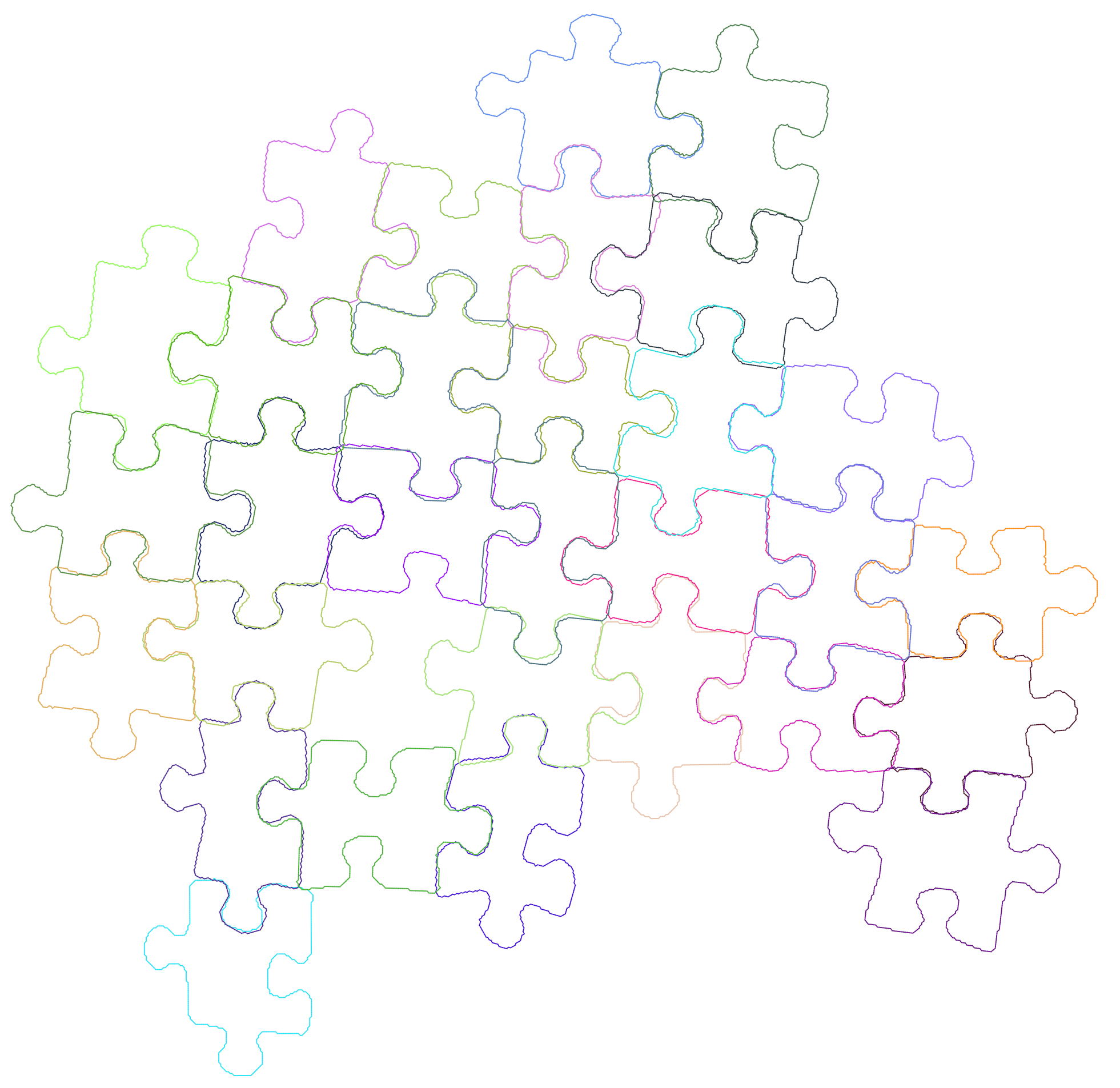

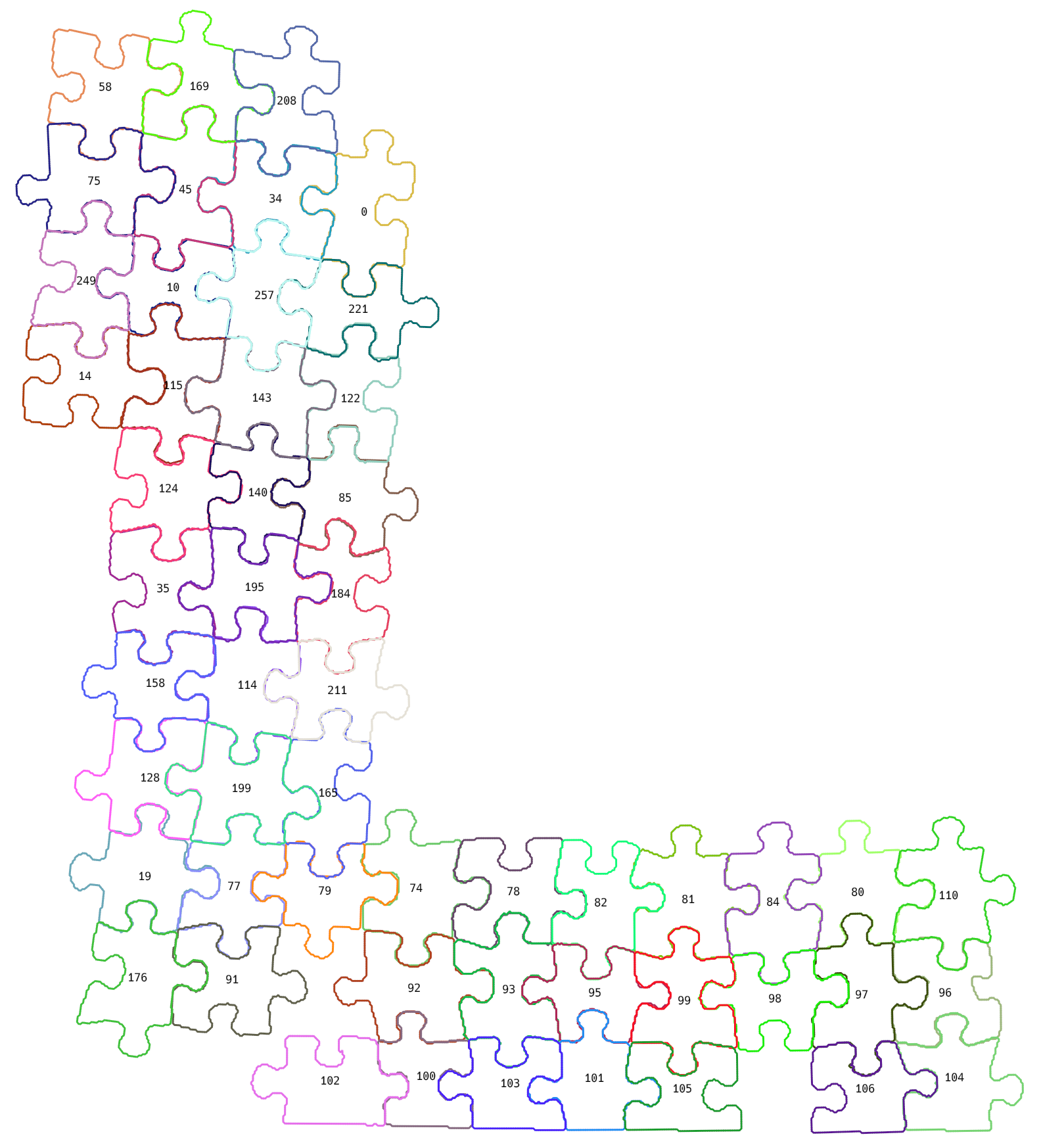

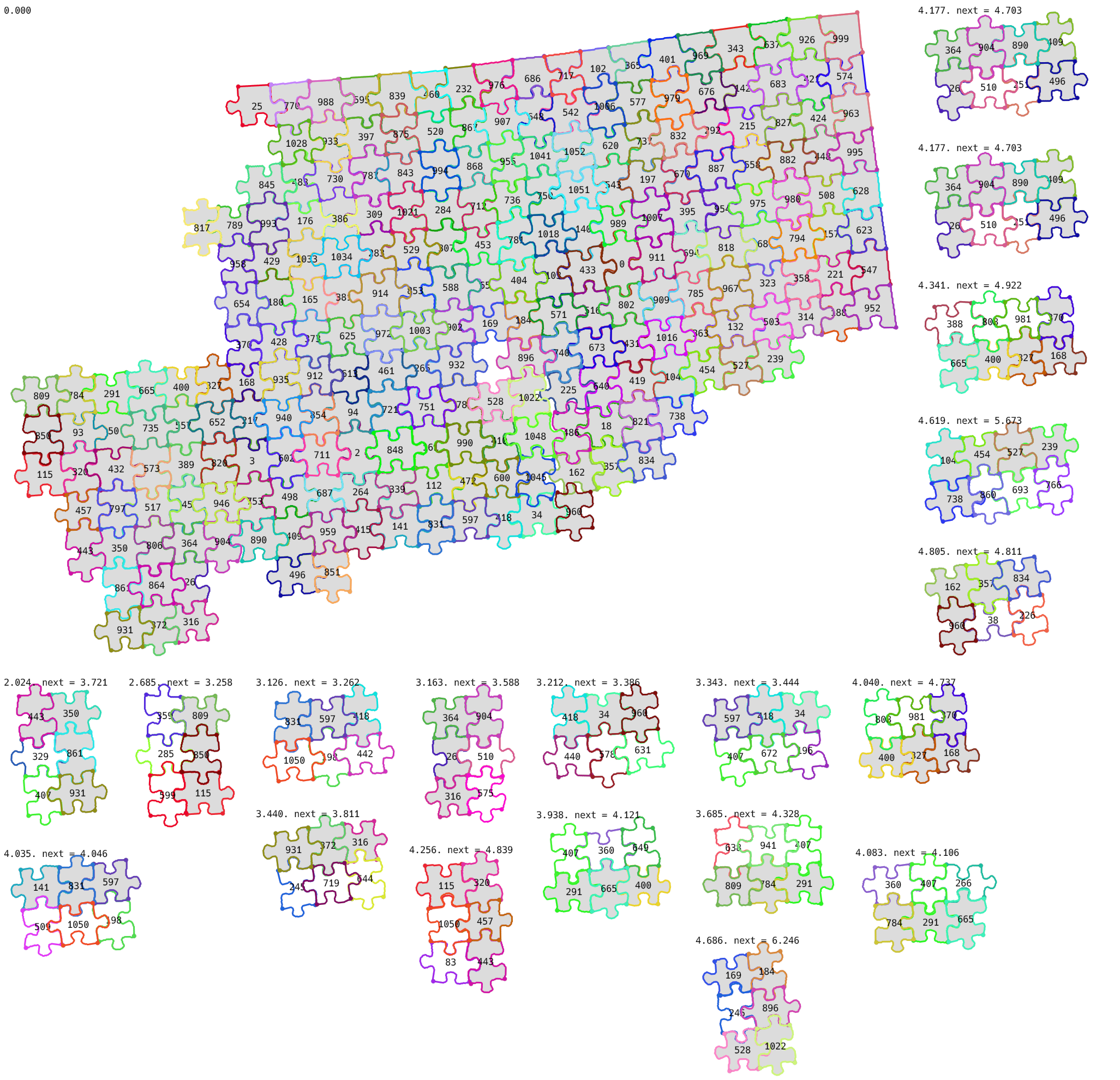

Playing around with different constants in the evolutionary algorithm gave this result:

My setup in real life looked like this:

After some time:

And later:

After joining all together and adding color pieces:

1000 pieces

I wanted to finish the story here, the puzzle is solved! But it wasn’t completely fair. Not all pieces were white, so the program only found several separate components, not solving the full puzzle. I didn’t want to implement color piece detection, instead, I decided to buy a jigsaw puzzle, which consists of white pieces only.

One tricky moment is that the new puzzle had 1000 pieces (compared to 500 in the previous one), but this should be just 2x harder, right?

Well, no.

First, in the previous puzzle, only half of the pieces were white, so it is 4x harder.

Second, complexity is not linear. Let’s look at an artificial example. Let’s say we have 250 pieces, and for each piece, there are 10 reasonable candidates to join it with. Say, we want to build a 2x2 block, already have 3 correct pieces, and are looking for a 4th one. A new piece has two edges, so we can pick 10 candidates based on one edge, and another 10 candidates based on the other edge, and only look at the intersection of those two sets. With quite a high probability intersection will only consist of one option.

But what happens if we have 1000 pieces? Then we have 40 different candidates for each edge. And the intersection of two random sets of 40 pieces quite often will not have exactly one piece. And here the problem comes. If on average we have less than one candidate, we can just iteratively solve the puzzle by adding pieces one by one. But if we have more than one candidate, we need to recursively check several of them. And after several steps, the number of reasonable options will be exponentially big.

There are at least two things, which we can optimize.

- Improve the score function to reduce the number of reasonable candidates.

- Improve the graph search algorithm. We can solve it not one by one, but do something smarter.

But all of this is just a theoretical discussion, let’s look at what happens in real life.

Reality

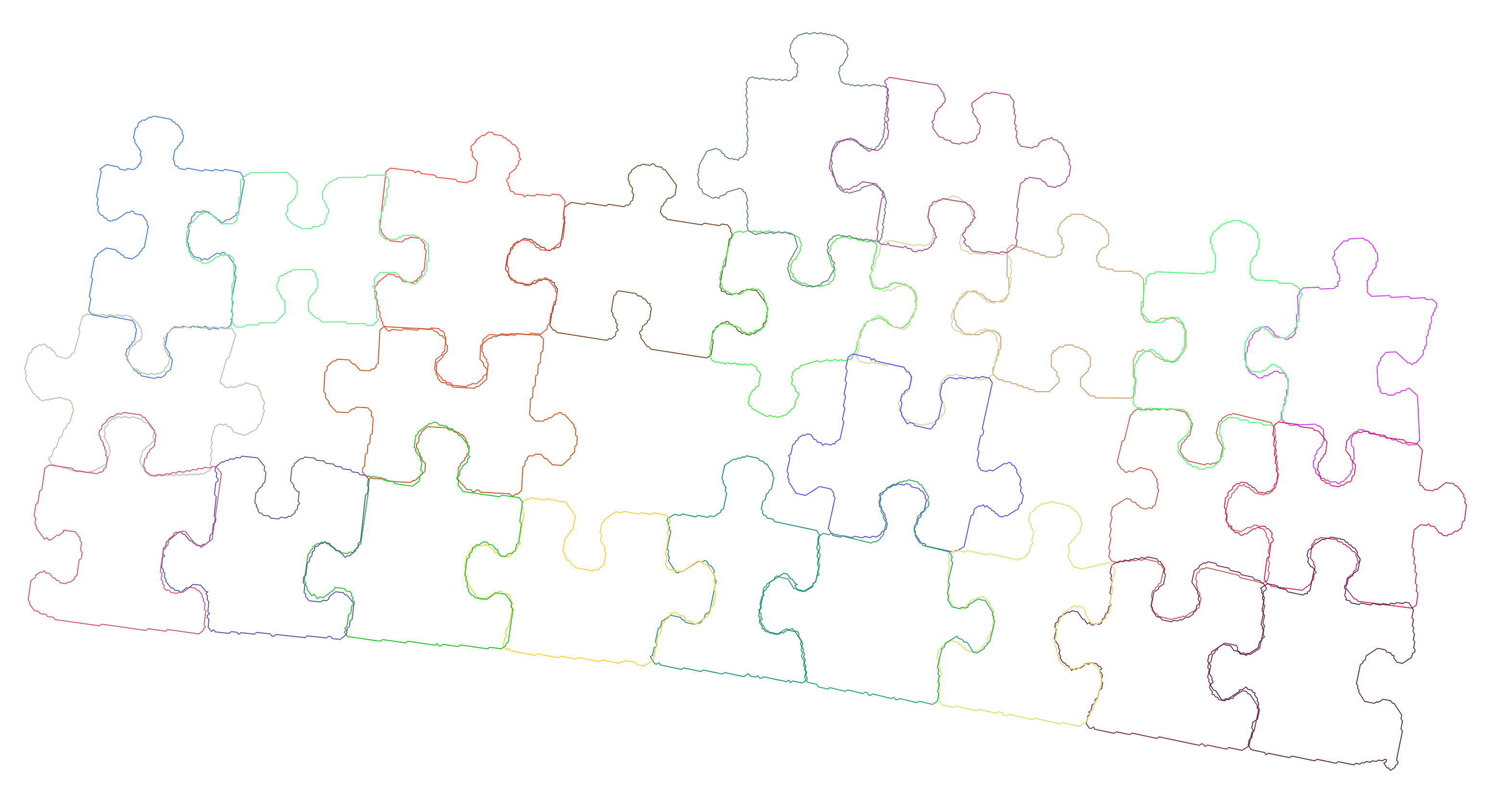

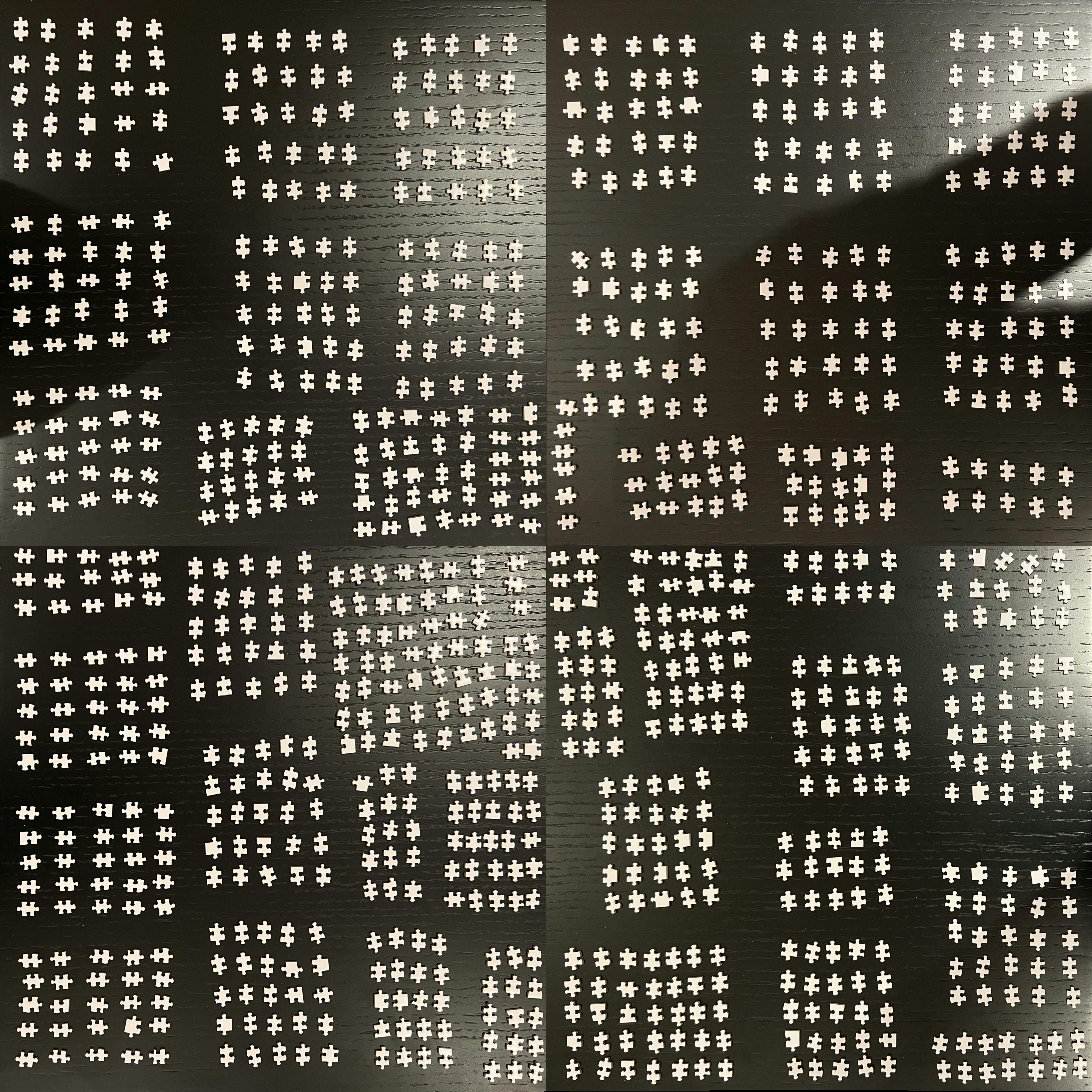

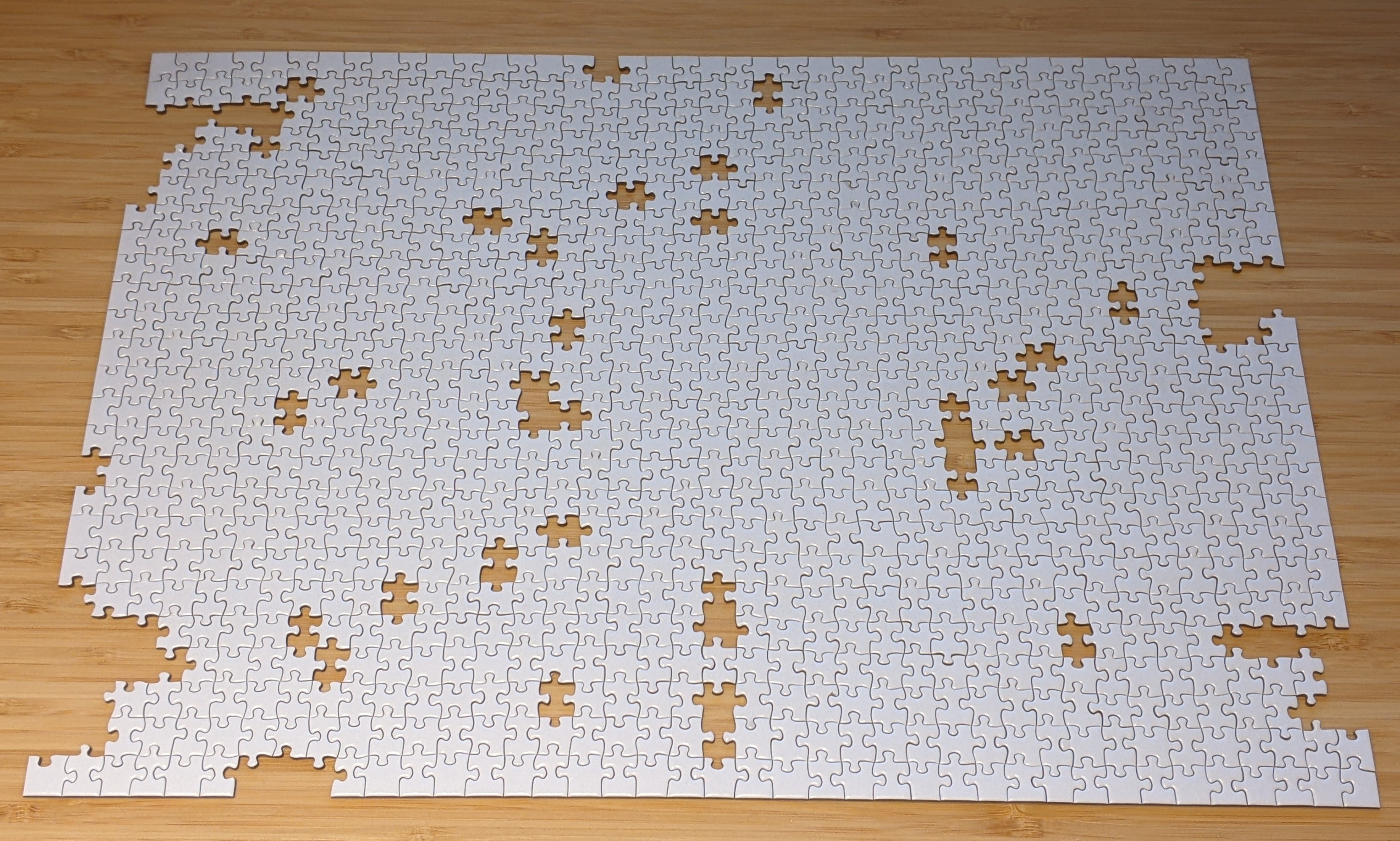

I put all the pieces on the table and took a picture with my phone:

It became clear that precision is very bad. New pieces are much smaller, but the number of pixels in the picture is still the same. So each piece has a smaller number of pixels, and it will be much harder to find the correct pairs.

Ideally, I should take a separate picture of each piece, but, first of all, it is not cool. Second, it takes a lot of time. So I decided to do something in the middle. I split the table into four parts, took separate photos of each of them, and then joined them together. After rescaling it looked like this:

New pieces are much smaller, but they also have bigger heights. So for pieces not in the center of the photo, we can see the border of the piece, which we shouldn’t count during matching. But after tweaking the piece detection algorithm it worked pretty well.

Does it work?

As I said before, in the case of 1000 pieces, it is much harder to find the solution, but it should be possible to find at least some good pairs, right?

I started from one corner and pretty quickly found two correct neighbors. Luckily, it was almost always possible to tell if two pieces fit together in the real world. So I could test what my program suggests.

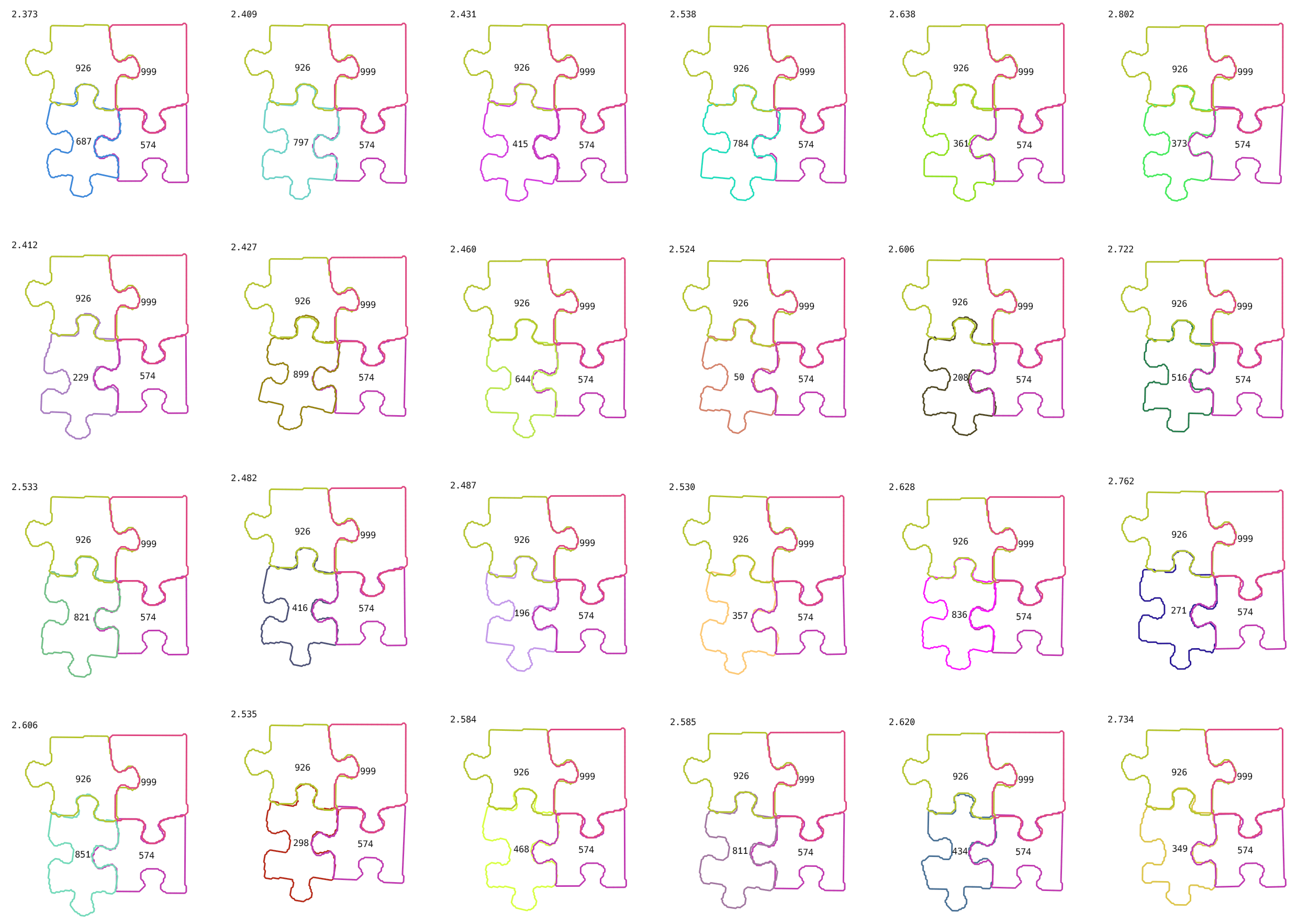

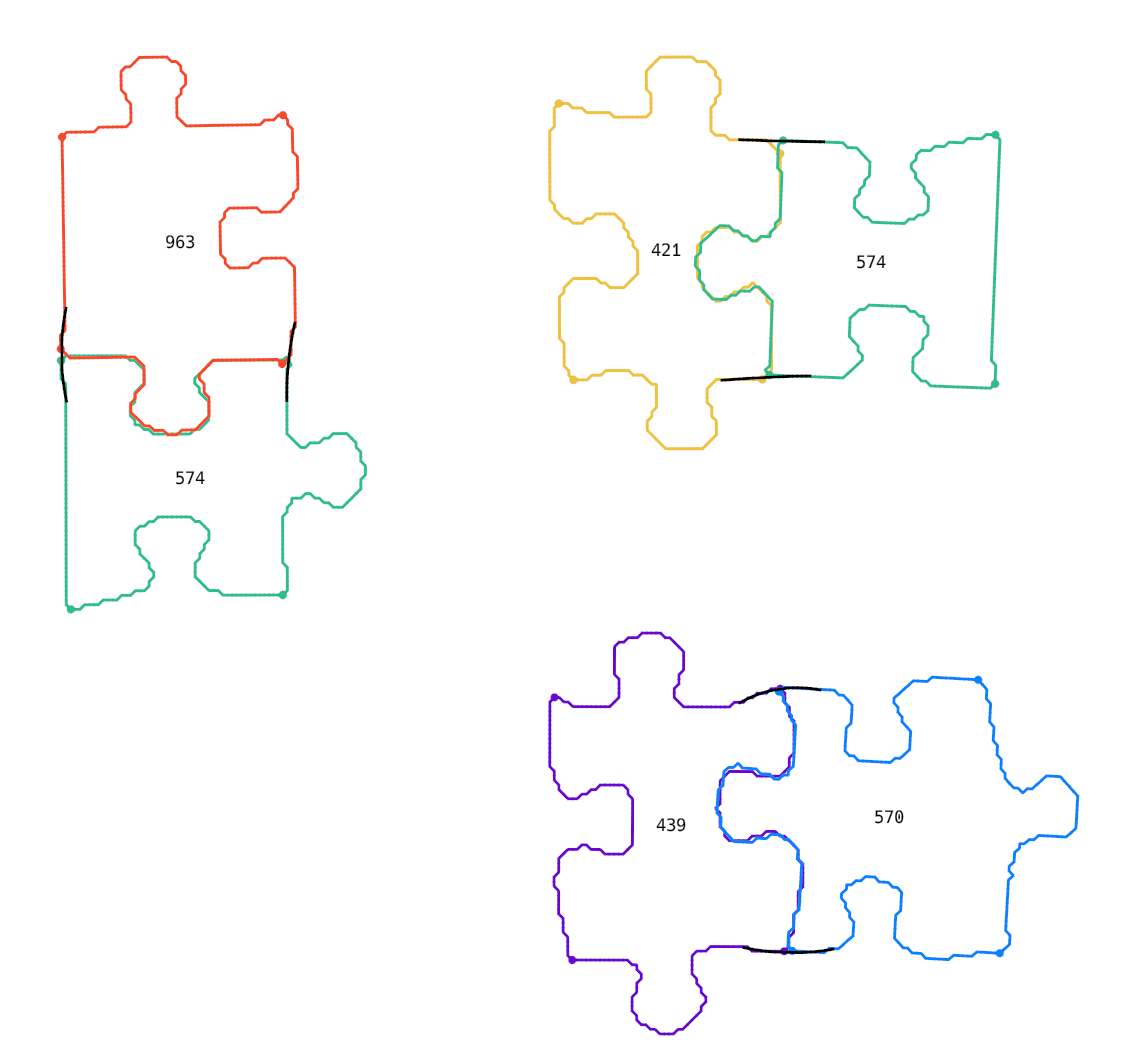

Finding the 4th piece of the 2x2 corner was very hard. You can see some options in the picture. I knew that pieces #999, #926, and #574 were correct. I tried all possible options for the 4th piece and sorted them by score. Could you guess the correct one?

You can guess that some of them are wrong, but there are a lot of really possible options. I tried all of the options from the picture, and none of them worked! It turned out the correct answer didn’t even get to the top 24.

Remember we discussed a theoretical example, when we have more than one candidate for each position, and the number of options to consider will exponentially grow? Well, we need to consider more than 24 options for each position.

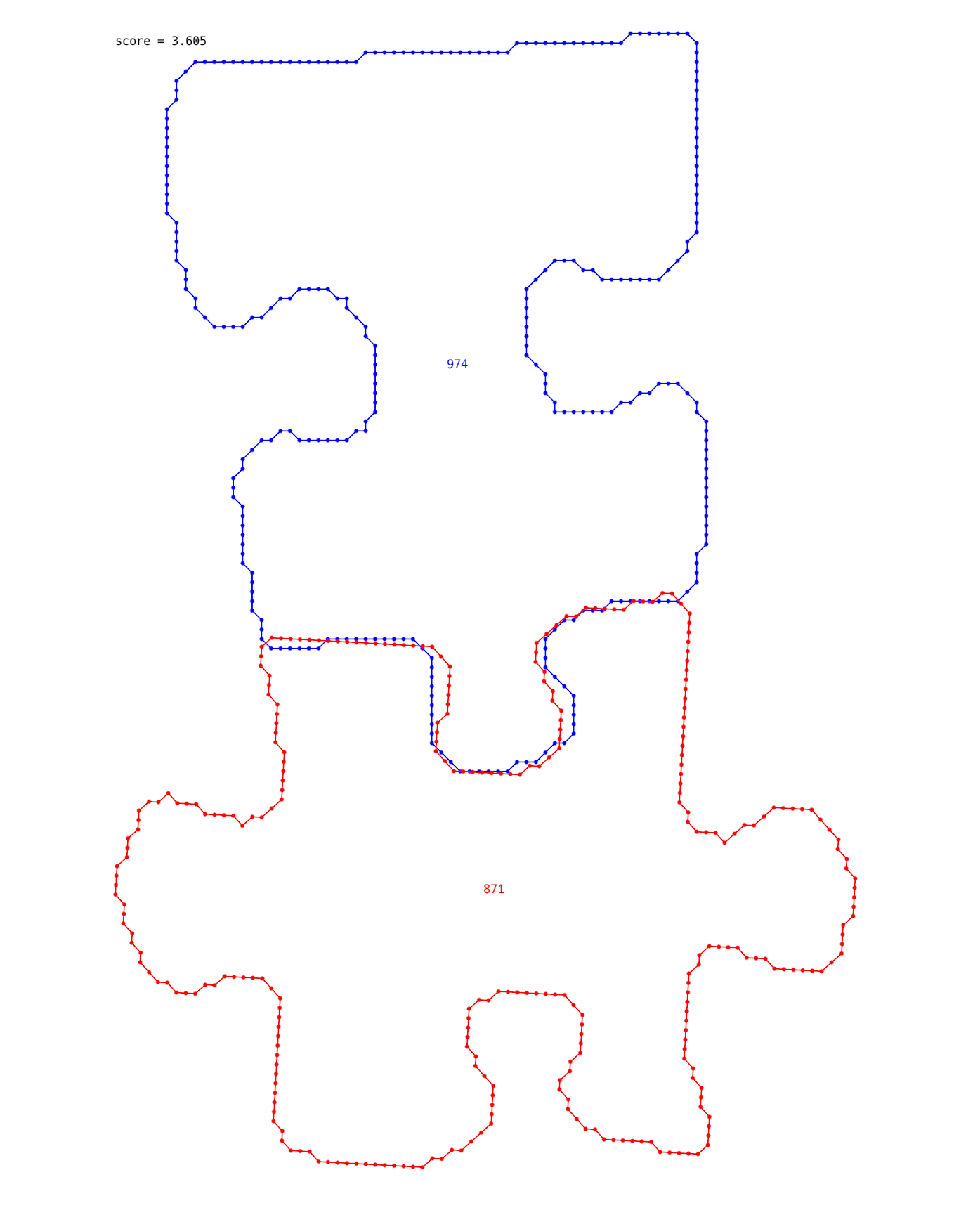

One more example, which I saw. Let’s say we have piece #974, we want to find a good match for it, and sorted all other candidates by the score. It turns out that the correct match (#861) is in the 350th position on this list.

These are extreme examples and in some cases, a good match is in the first place, but most of the cases were very hard.

Better score function

In the previous examples, humans can understand that some pieces don’t fit at all, but the program doesn’t understand it. Why does it happen?

One reason is how I handled the corners of the piece. Humans understand that the corners of one piece should be in exactly the same locations as the corners of the other piece. Moreover, if you draw tangents near the corners of two pieces, they should be almost equal. It is easy to check for a human, but how to express it in the program (especially when you have pixels, and they don’t really lie on an exact line)?

I wrote a code, which takes the last several pixels of two pieces and tries to find a line, which approximates them the best. If it finds a good approximation, two pieces probably fit. It worked better than before, and I found some more correct pairs, but there were a lot of constants in the code, which were picked randomly. Maybe we can choose them in a smarter way?

Are we machine learning yet?

How to choose better constants (how many pixels take from each side, what should be the weight of the line approximation score, …) in our algorithm?

Well, I found some correct pairs, and for each of them, I can calculate the score function and the position in the sorted list of best matches. We want to minimize positions for all of them. But obviously, we can’t minimize all of them at the same time. We can come up with some reasonable overall score function (e.g. sum of logarithms of positions), and try to minimize it by tweaking constants.

Probably you can write some smart algorithm for finding the best constants, but I just tried to change them manually and see if the score improves.

Linear functions

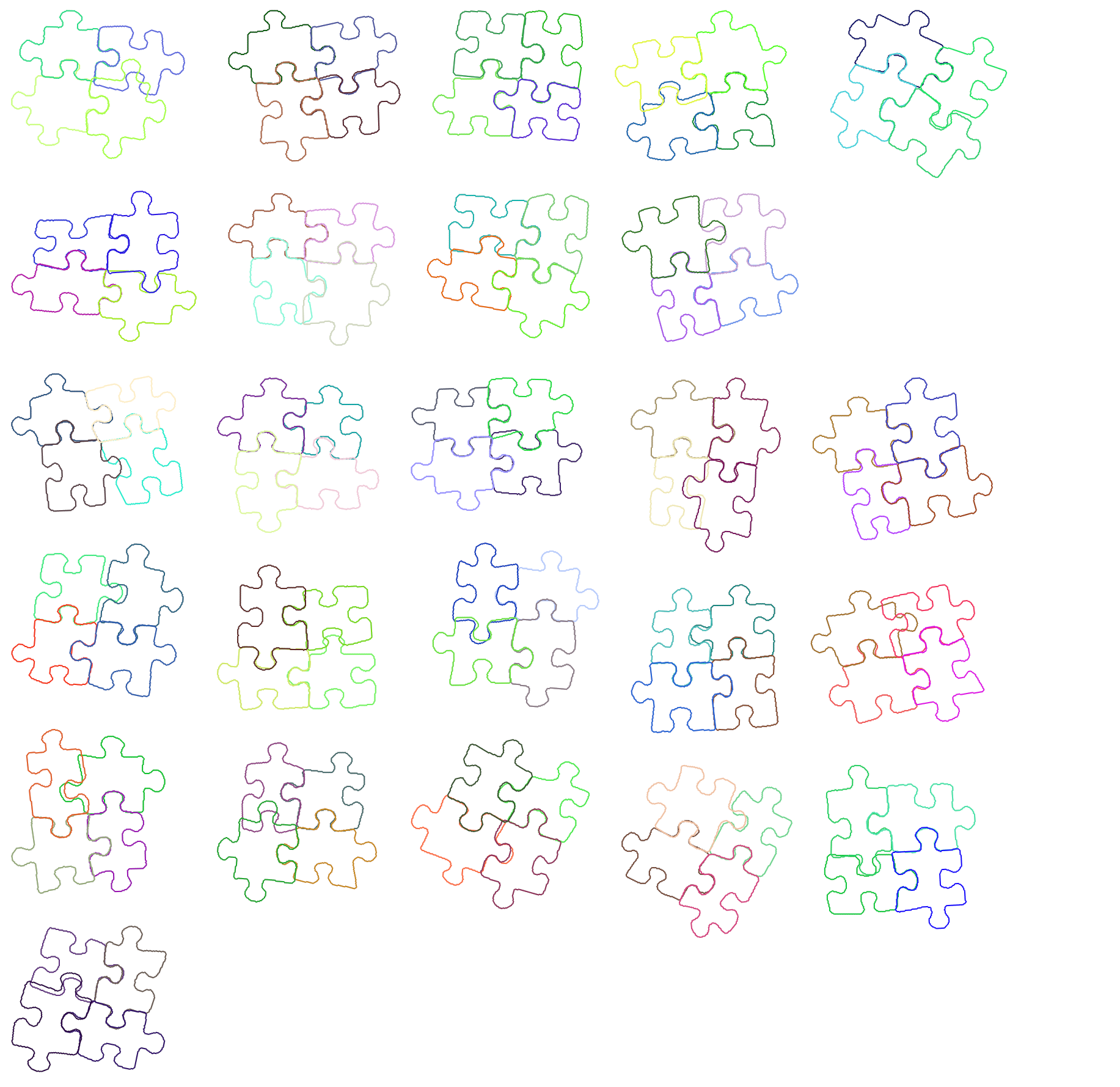

Sometimes I saw pairs of pieces, which fit perfectly, but with a bad score. Here is one example:

You probably can guess why it happens. We draw a straight line to check if the corners match, but we fail. Here we actually need some curves.

So I implemented a thing called spline interpolation and it worked better:

Change the paradigm

After fixing the score function, finding each next piece became a much easier task, but solving the whole puzzle at once still looked like an impossible task.

Basically, there is no way for a program to check if it found the correct piece or not. You can think that after using the wrong piece it could realize later that it was wrong when it can’t find a good next one. But in fact, instead, it will probably just choose the next piece incorrectly as well.

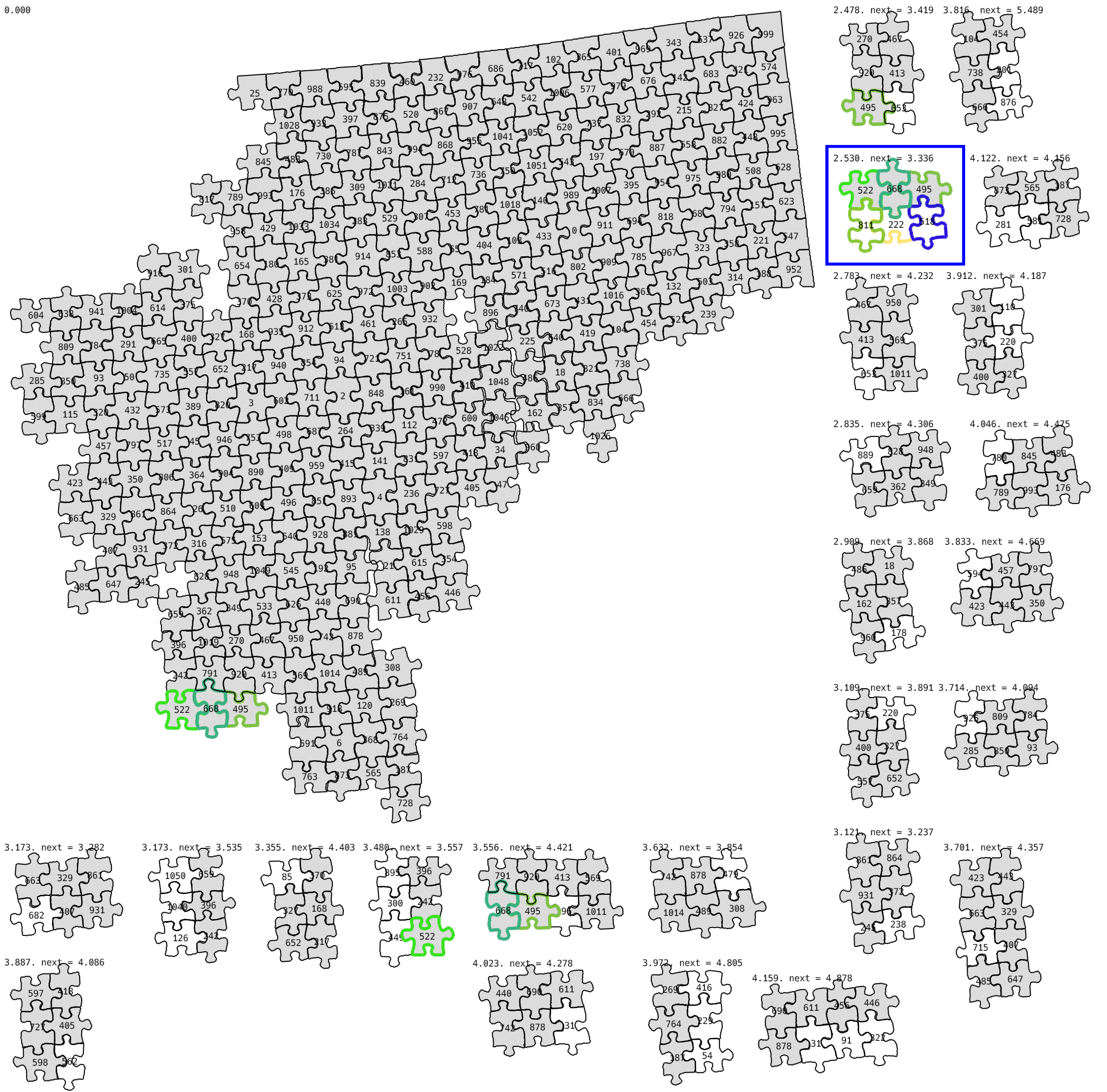

So instead of solving the full puzzle at once, I decided to change it to interactive mode. The program suggests adding some pieces, human tries, and tells if that was successful. After that program updates the currently built picture and suggests the next step.

The main interface looked like this:

It searched for three consecutive pieces and tried to add at most 3 more (some could be already present) to get a 2x3 figure. And for each possible location choose the best possible option.

When the already built part became bigger, it became hard to understand where a suggestion should be applied, so I modified the interface to show it:

Later instead of using a fixed 2x3 pattern, I started searching for just 3 new connected pieces, which have already present neighbors.

Performance optimizations

One problem, which comes with the big number of pieces, is that everything becomes slow, and we need to fix it.

Every time we add a new piece to the solution, we need to run local optimizations on all of them to put them on the surface. So instead we can just run local optimizations on new ones and some neighbors.

When more pieces are already present, there are more positions, where you can put a new one, so more options to check. We need to add caches for states, which were already checked.

One thing, which helped a lot, is the rayon library in Rust. Whenever you have a loop, you can replace iter() with par_iter() and it works 8 (or how many cores do you have) times faster! This is magic! Obviously, you need to not modify the shared state in that loop, but usually, it is easy to rewrite the code in a way that doesn’t do it.

The end

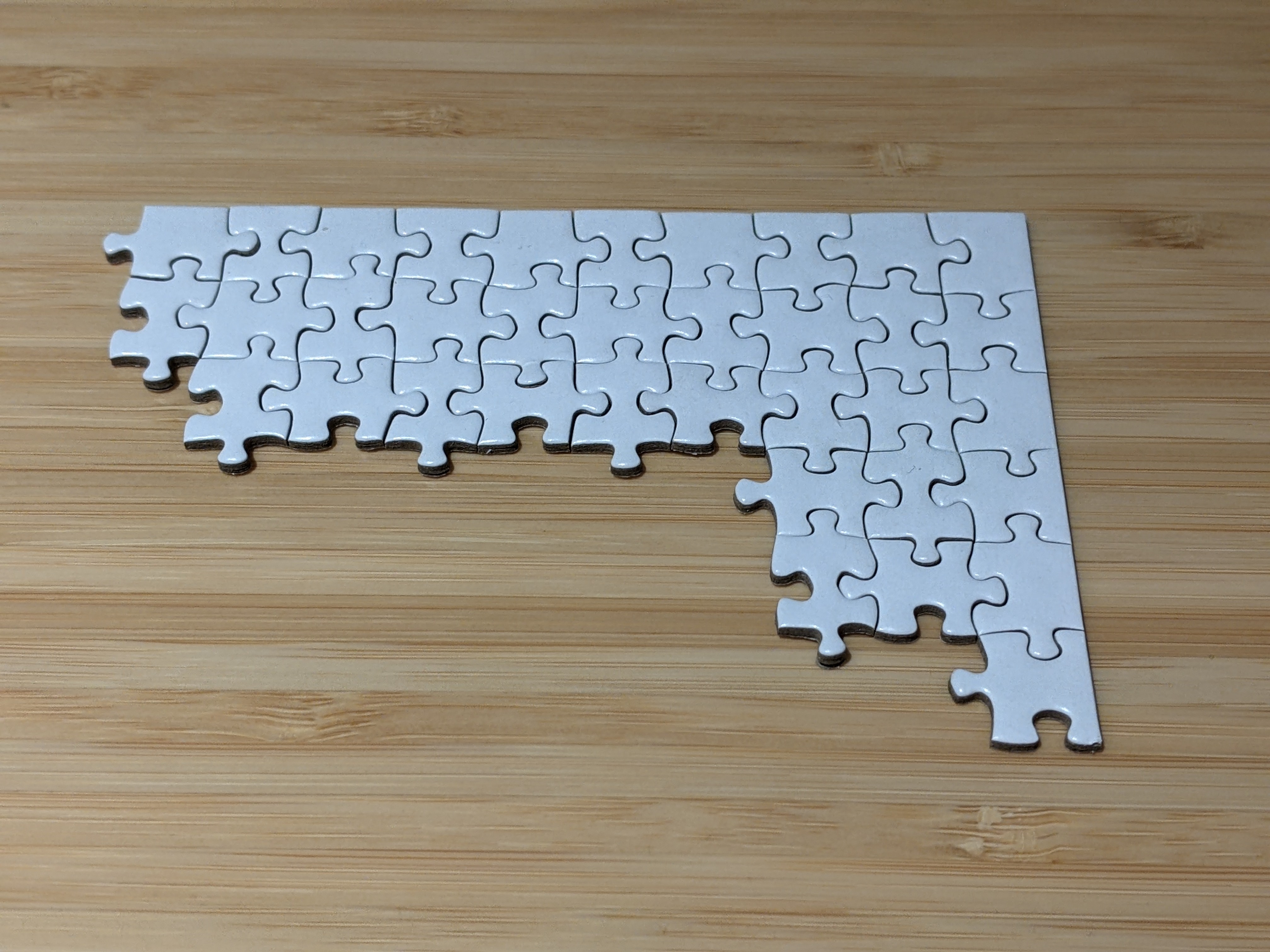

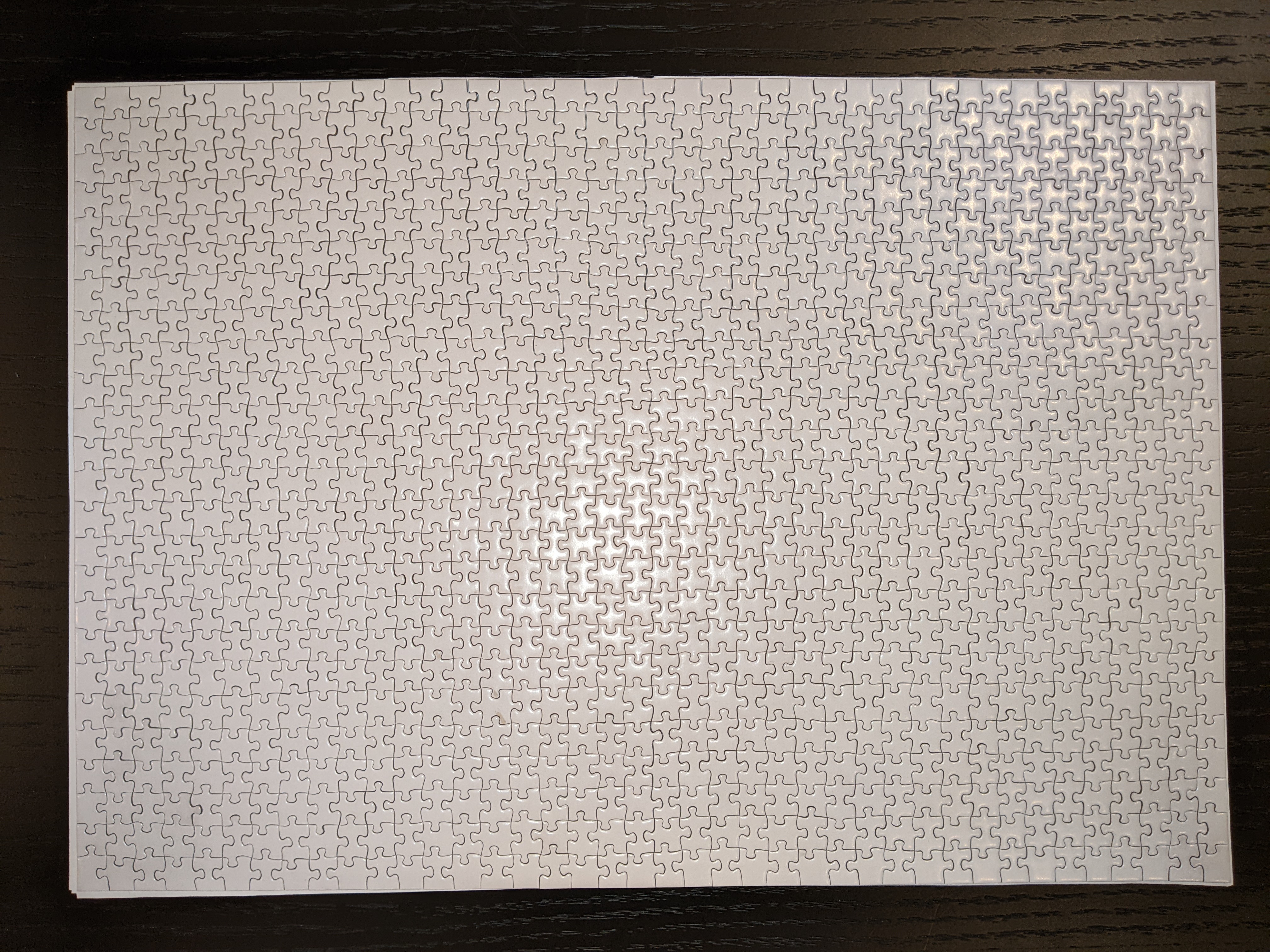

In the end, I built almost the full picture (without some pieces, which were not parsed properly from the photo) by program suggestions:

And put all other pieces manually:

It is a little bit sad that the program can’t solve the full puzzle in advance and requires a human to check the result, but I think with better picture quality it is definitely possible.

Check out the source code if you want.

If you read till this point and know Russian, consider subscribing to my Telegram channel with similar posts: https://t.me/bminaiev_blog.