Round 3 of Meta Hacker Cup 2022 finished a couple of days ago. Today I’ll talk about the hardest problem from that round, which was solved only by 3 people. The problem is quite classical, so basically after reading the problem statement, experienced competitive programmers already know what they need to write, but the amount of the code is pretty big, and almost nobody likes geometry problems, so this probably explains why there are so few accepted solutions.

Let me describe the main part of the problem. You are given n polygons, which don’t intersect (and even touch) with each other, but polygons could be fully enclosed in another. You need to answer q queries one by one. Each query is one point, and you need to find the smallest (by area) polygon (out of the given in the initial input), which contains this point. The total number of vertices in all polygons is around one million, and the total number of queries is also around one million. So you can’t just check all pairs of queries and polygons.

The classical algorithm for this task is doing a sweep-line by X coordinate and maintaining a set of all edges, which contains the current X coordinate. The set itself should be sorted by Y coordinate. You also need to store all the revisions of this set, so when you receive a query (x, y), you can find a revision for a specific x, and find a lower bound for y in the set. Because you want to efficiently store revisions, you can’t just use a built-in std::set, you need to use a persistent treap or a similar data structure. You can find the details of this algorithm (a simplified offline version of it) in cp-algorithms. But even without reading this article, you probably already understood why there were so few accepted solutions to the problem from Hacker Cup.

I knew this algorithm before the round, but I don’t like writing treaps during the contests, so I didn’t manage to implement it in time (thankfully, solving all other problems was enough to advance to the Finals). After the round, I talked to Pavel, and he showed me another algorithm, which could be used for this problem. I didn’t know it before, it has worse time complexity (\(O(\log^2 n)\) per query, \(O(n \log n)\) memory), but I think it is easier to implement. I don’t think it is very well known. The only place, I could find, where it is mentioned, is in this paper, so I decided to share it here.

Main idea

Note. We say our polygons don’t include the boundary, so if the query point exactly lies on the boundary of some polygon, we return the parent of that polygon. It is possible to include boundaries, but it requires some carefulness.

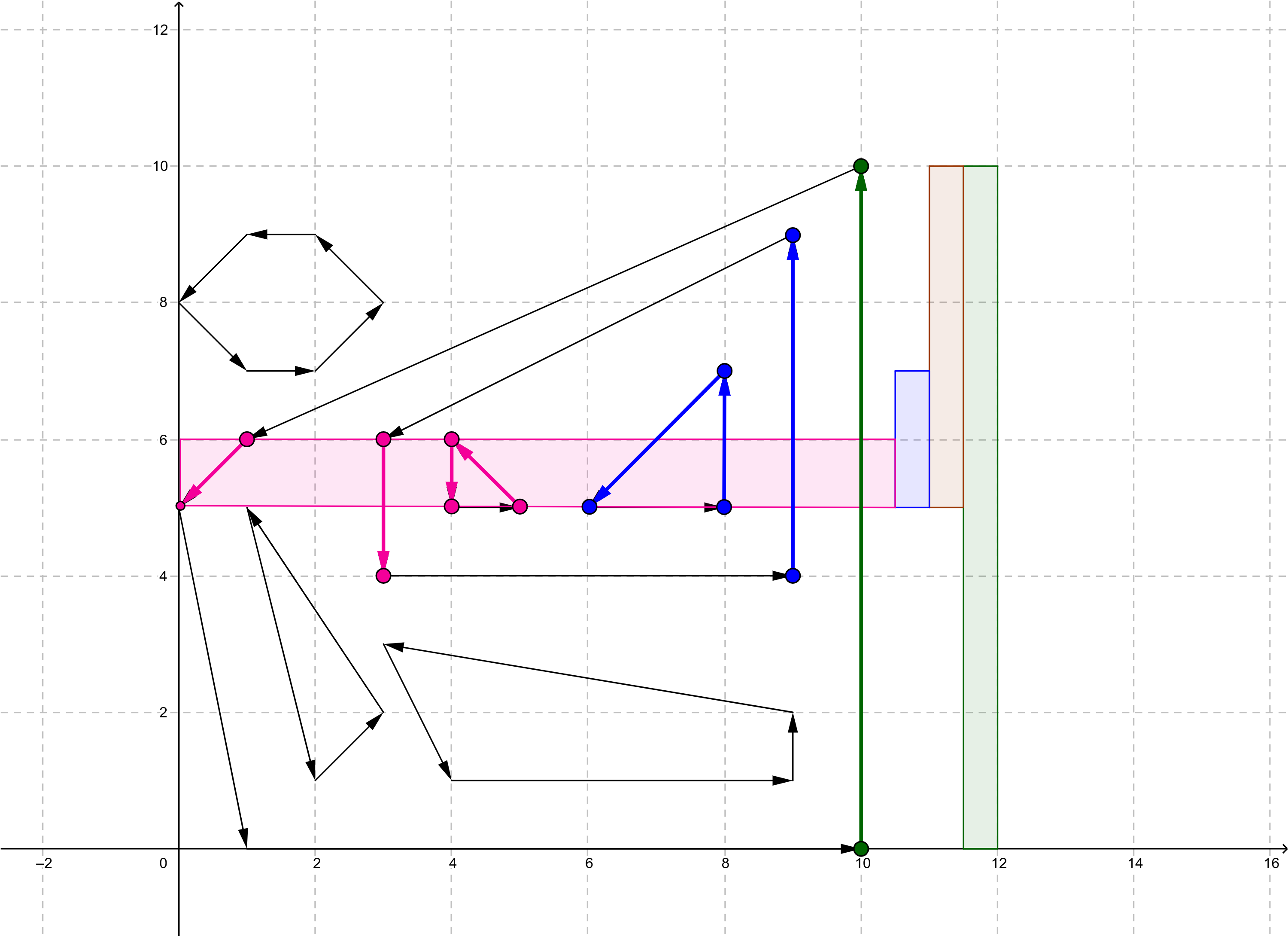

So we have a point, and we want to find in which polygon it is located. Let’s draw a ray from a point to the left, and find the first edge, which it intersects. There could be two cases:

- Our point is inside the polygon, which contains this edge.

- Our point is just outside of the polygon, which contains this edge. In this case, our point is inside the “parent” polygon of the one, which we just found.

How to determine what is our case? Let’s say we stored the vertices of our polygons in the counter-clockwise order. Then if the edge goes from top to bottom, the point is inside the polygon. If from bottom to top — outside of it.

We ignore edges, which have the same y coordinate of ends.

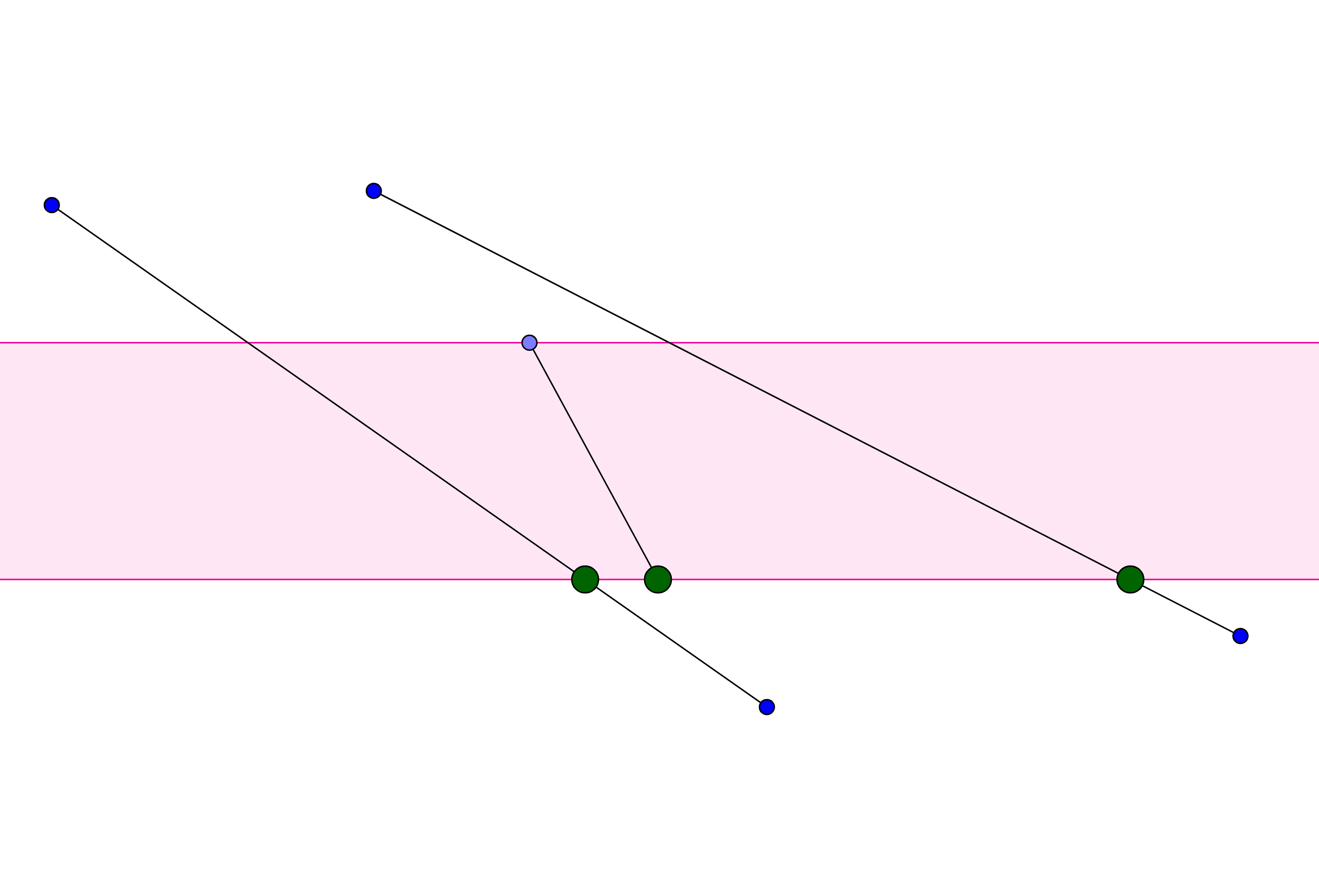

How to efficiently find the first edge to the left of the point? Let’s first discuss how to efficiently find all edges, which intersect line y=C. We can maintain a segment tree by Y coordinate. Each node of the segment tree corresponds to some segment min_y..max_y of y coordinates. In the node, we store a vector of all segments, which fully covers this range of y coordinates. Each edge is added to \(O(\log n)\) nodes, so overall \(O(n \log n)\) memory is used.

Here is a basic type for storing edges.

#[derive(Clone, Copy, PartialEq, Eq, Debug)]

struct Segment {

fr: Point,

to: Point,

polygon_id: usize,

}

impl Segment {

pub fn get_lower_higher(&self) -> (Point, Point) {

if self.fr.y < self.to.y {

(self.fr, self.to)

} else {

(self.to, self.fr)

}

}

}

And let’s start implementing the main PointLocation structure. Points y coordinates could be arbitrarily large, so we need to compress coordinates (and store them in the all_y field).

pub struct PointLocation {

all_y: Vec<i64>,

tree_nodes: Vec<Vec<Segment>>,

...

}

impl PointLocation {

// vertices should be specified in ccw order

pub fn new(polygons: &[Vec<Point>]) -> Self {

let mut all_y: Vec<i64> = polygons

.iter()

.flat_map(|poly| poly.iter().map(|p| p.y))

.collect();

all_y.sort();

all_y.dedup();

let tree_nodes_cnt = all_y.len().next_power_of_two() * 2;

let mut res = Self {

all_y,

tree_nodes: vec![vec![]; tree_nodes_cnt],

...

};

for (polygon_id, polygon) in polygons.iter().enumerate() {

for i in 0..polygon.len() {

let segment = Segment {

fr: polygon[i],

to: polygon[if i + 1 == polygon.len() { 0 } else { i + 1 }],

polygon_id,

};

res.add_segment(0, 0, res.all_y.len() - 1, &segment);

}

}

...

res

}

fn add_segment(&mut self, tree_v: usize, l: usize, r: usize, segment: &Segment) {

let min_y = self.all_y[l];

let max_y = self.all_y[r];

let (lower, higher) = segment.get_lower_higher();

if lower.y <= min_y && higher.y >= max_y {

self.tree_nodes[tree_v].push(segment.clone());

} else if lower.y >= max_y || higher.y <= min_y {

return;

} else {

let m = (l + r) >> 1;

self.add_segment(tree_v * 2 + 1, l, m, segment);

self.add_segment(tree_v * 2 + 2, m, r, segment);

}

}

}

To iterate over all edges, which intersect some y=C, we need to just recursively go down by segment tree as we usually do, and list all edges in each node, which we visit.

Comparator

Instead of iterating over all edges, which intersect y=C, we want to efficiently find the closest one to the left. We can sort all edges in each node of the segment tree by the X coordinate, and then do a binary search to find the closest one. If we do that, the overall complexity for each query will be \(O(\log^2 n)\), as we need to run a binary search on \(O(\log n)\) segment tree nodes. How to do a binary search? We just want to know, if the point is to the left or to the right of the edge. This is done by a simple vector (cross) product:

impl Segment {

pub fn cmp_p(&self, p: Point) -> Ordering {

let (lower, higher) = self.get_lower_higher();

if p.y < lower.y || p.y > higher.y {

return Ordering::Equal;

}

Point::vect_mul(&lower, &higher, &p).cmp(&0)

}

}

There is a special case for a point with too big or too small y coordinate. During the binary search, it should never happen as we only do it over the edges, which intersect our y coordinate. But it will help us later.

To do a binary search, we should sort all edges inside each node of the segment tree. But what comparator should we use? They should be sorted in the order of increasing X coordinates, but it is a little bit tricky. We have an invariant that each edge stored in the node covers at least segment y_min..y_max of that node. For each edge, we can compute an x coordinate of an intersection of this edge and y_min and then sort by that x.

But computing this x coordinate requires floating point arithmetic, which should be avoided whenever possible. So instead we can write comparator differently. When we want to compare segment (p1, p2) with (p3, p4), it is always possible to find one point of [p1, p2, p3, p4], such that the y coordinate of that point is covered by another segment. When we found this point, we can compare it with another segment using the same comparator as in the binary search.

It is possible to prove that this comparator and floating point one returns the same result.

The final version of the comparator looks like this:

impl Ord for Segment {

fn cmp(&self, other: &Self) -> Ordering {

self.cmp_p(other.fr)

.then_with(|| self.cmp_p(other.to))

.then_with(|| other.cmp_p(self.fr).reverse())

.then_with(|| other.cmp_p(self.to).reverse())

}

}

then_with tries the next possibility if the previous comparator returned Ordering::Equal. It is the moment when our special case from cmp_p helps.

Point location

The only thing left is to implement the searching logic. But it is very similar to regular segment tree implementation. I implemented it without recursion just to speed it up a little bit.

pub fn locate_point(&self, p: Point) -> Option<usize> {

let mut segment: Option<Segment> = None;

let mut tree_v = 0;

let (mut l, mut r) = (0, self.all_y.len() - 1);

loop {

let min_y = self.all_y[l];

let max_y = self.all_y[r];

if p.y < min_y || p.y > max_y {

break;

}

if let Some(idx) = binary_search_last_true(0..self.tree_nodes[tree_v].len(), |i| {

self.tree_nodes[tree_v][i].cmp_p(p) == Ordering::Less

}) {

let new_segment = self.tree_nodes[tree_v][idx];

if segment.is_none() || segment.unwrap().cmp(&new_segment) == Ordering::Less {

segment = Some(new_segment);

}

}

if l + 1 < r {

let m = (l + r) >> 1;

let mid_y = self.all_y[m];

if p.y < mid_y {

tree_v = tree_v * 2 + 1;

r = m;

} else {

tree_v = tree_v * 2 + 2;

l = m;

}

} else {

break;

}

}

segment.and_then(|segment| {

if segment.fr.y < segment.to.y {

self.parents[segment.polygon_id]

} else {

Some(segment.polygon_id)

}

})

}

One thing, which I haven’t covered is self.parents. For each i, it stores the smallest polygon self.parents[i], which contains polygon i. How do we compute it? It is very easy. We can just run the locate_point function on the leftmost point of that polygon. The only tricky moment is that we need to call it in the correct order to make sure that we already computed parents for all polygons to the left of it.

impl PointLocation {

// vertices should be specified in ccw order

pub fn new(polygons: &[Vec<Point>]) -> Self {

...

for node in res.tree_nodes.iter_mut() {

node.sort();

}

let mut polygons_left_points: Vec<_> = polygons

.iter()

.enumerate()

.map(|(id, poly)| (poly.iter().min().unwrap(), id))

.collect();

polygons_left_points.sort();

for (&p, polygon_id) in polygons_left_points.into_iter() {

res.parents[polygon_id] = res.locate_point(p);

}

res

}

}

Conclusion

I think this algorithm is easier to implement than a treap-based solution. The only tricky moment is comparators. But they are basically the same for both solutions. Everything else is just a regular segment tree code. The full code for the HackerCup problem could be found here.

It has \(O(n \log^2 n)\) complexity, but in fact, it is pretty fast. My code solves the full dataset of the HackerCup problem under 5s on my laptop even in a single thread.

If you read till this point and know Russian, consider subscribing to my Telegram channel with similar posts: https://t.me/bminaiev_blog.