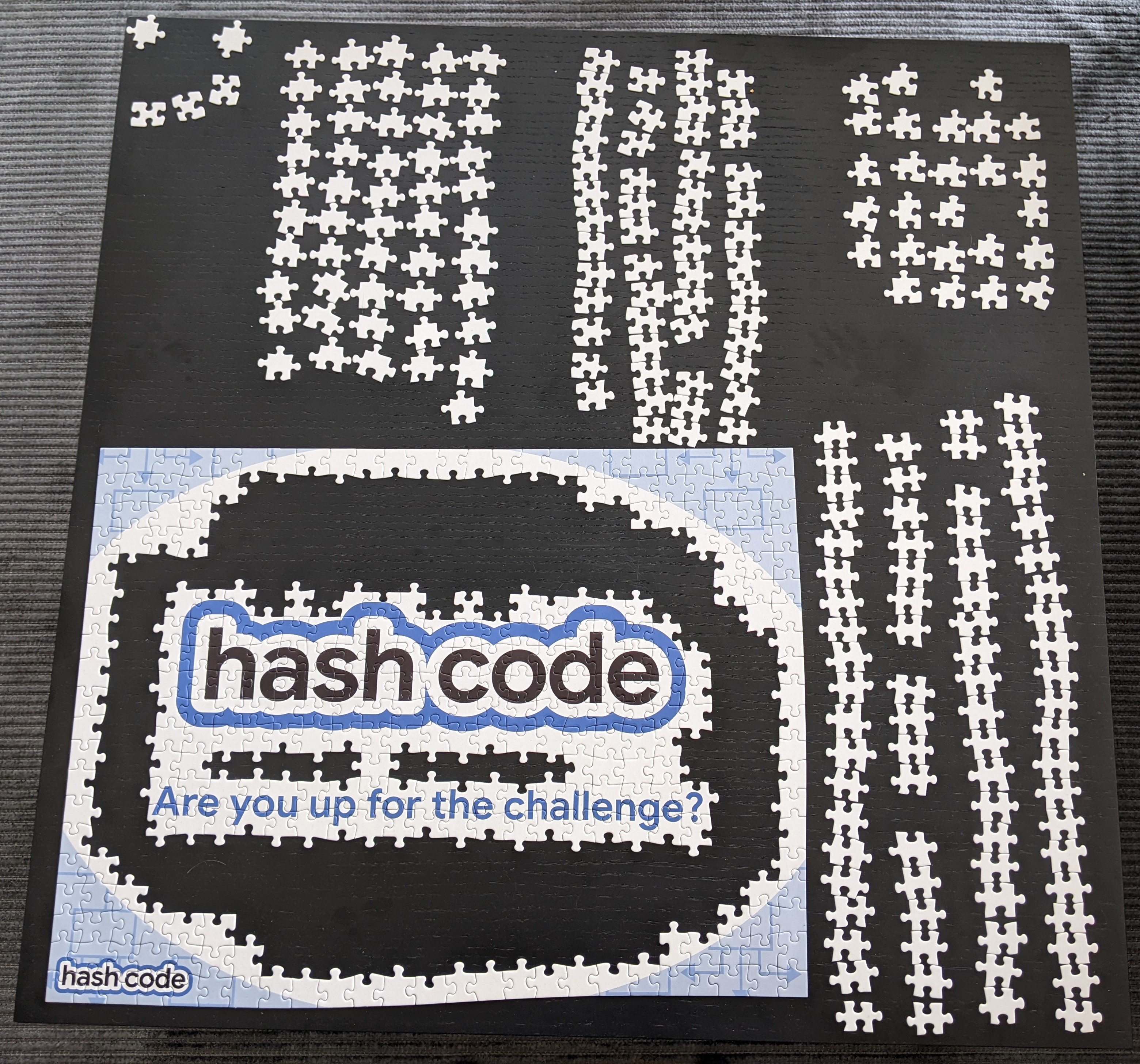

I participate in a lot of programming competitions and usually, if you show good results, organizers send you some prizes. Typically it is just t-shirts, but at some point, you have too many of them, so you had to make a bed cover from them. But sometimes prizes are more interesting. This time Google HashCode organizers sent a jigsaw puzzle if you advanced to the finals. That was cool, so I decided to solve it.

It went pretty well until I got into trouble. I finished a big part of the puzzle, but all the left pieces were completely white. I divided all of them into groups by their shape, but still for each specific position you usually need to try all pieces from two or three groups. It was insanely hard for me to find each next correct piece, and also didn’t bring much joy. I found only several new pieces over the next couple of evenings and decided to stop. I was thinking “I am a software engineer! I shouldn’t solve it by hand! I should write a program, which solves it!”. At that point, I took a picture on my phone and put all the pieces back in the box, so I can use a table for other stuff.

Several months later…

The difference between the idea of writing a program for solving a puzzle, and actually writing a program, is quite big, but later I had some free time, so I really decided to do it. Back then I didn’t actually know how hard it would be and if it was actually possible. But I had a rough plan.

- Crop/reshape the picture. We want to be able to check if two pieces fit together, so we need to know their exact shapes. But when you take a picture, far objects are smaller in terms of pixels, so we need to fix it.

- Detect pieces. We need to separate pieces from the background (and also from other pieces, if they are connected).

- Detect borders. When you fit pieces, you actually don’t care about the full piece, you only need to fit the borders.

- Detect corners. This was an optional point of the plan. From a human standpoint, you think about the pieces as something, which has four sides, and you fit one side of the piece with another side of another piece. But from a computer standpoint, it can try all possible fitting positions. Fit pairs of pieces. For each pair of pieces, for each pair of sides, I wanted to try to fit them, and calculate some score, which shows how well they fit.

- Find the solution. If we know how good pieces fit, we can forget about shapes and think just about a graph problem, where for each piece we need to find the best position (and rotation) in a grid to maximize the overall fit function.

- Show the solution. When positions in a grid are known, we need to come back to pieces with shapes and show them. Need to find the correct position and rotation for each piece, so they all fit together. It is also possible that one piece fits well with all the neighbors in terms of the score function, but there is no way to actually put it on a surface to achieve that score function with all neighbors at the same time.

Now, when I actually wrote down this plan, I realized how many details there are. But when I thought about it, it didn’t look that scary.

To make things even more fun, I decided to not use any existing smart libraries for computer vision and other stuff, and just work with an image as with a two-dimensional array of (r, g, b) values.

Reshaping the picture

Luckily I had a square table in the photo, so I could use its corners as base points for reshaping. Obviously, there are some programs, which could reshape the picture automatically, but I only started working on this project, had a lot of energy, and decided to implement it myself (don’t repeat my mistakes).

My idea was to make a GUI, which lets you pick four corners of a table with a mouse, and then do reshaping. I wanted to put corners of the table into corners of a new picture, and stretch everything else. It is easy to say “stretch”, but how do you do this in terms of pixels?

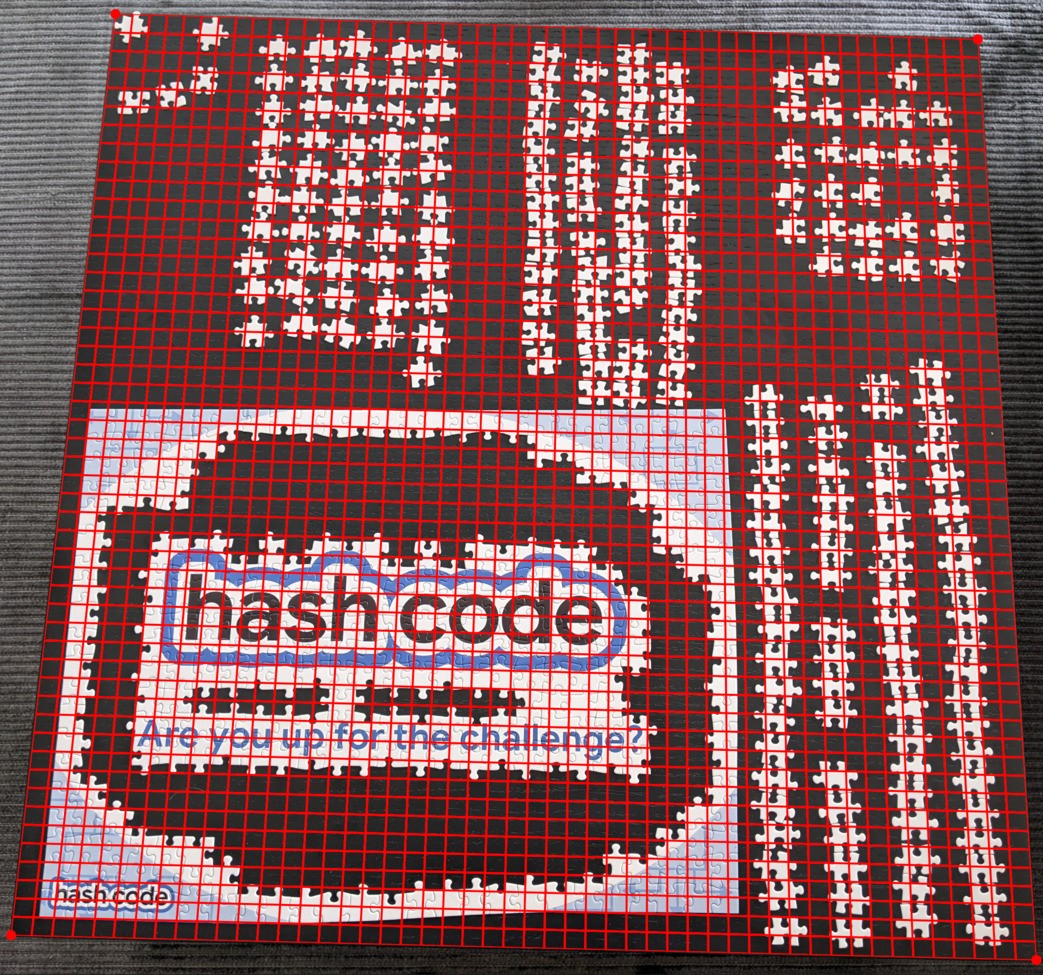

Let’s say we decided that the new picture will have a size 1000x1000. Then we can connect table corners via segments, split them into 1000 equal parts, and then connect points from opposite sides. Each quadrilateral will correspond to one pixel in a new picture. In the case of a 50x50 picture, it looks like this.

To calculate a color for each new pixel, we can iterate over all pixels inside the quadrilateral, and take an average. It is a little bit more complicated because some pixels could be partially inside several different quadrilaterals, but we can give them a weight proportional to the area of the intersection. We need to do some computational geometry, but in the end, we get a result, which seems pretty reasonable!

But…

This method works pretty well, except for one “but”. It doesn’t do what we need! From this transformation, we need one property. If we choose 4 points [p1, p2, p3, p4] and the distance (in real life) between p1 and p2 is the same as between p3 and p4, it should be the same in the generated picture. This property holds for corners of the table. But it doesn’t work for other points.

Funny enough, I didn’t realize the problem until I implemented all other parts of the algorithm and started testing it on real pieces, trying to fit pairs found by the algorithm, and didn’t succeed.

The issue comes from the fact that we split segments into 1000 equal parts. If we take a segment and look at the midpoint (calculated in terms of pixels), it will not have the same distance to two ends in a physical world. It will be closer to a point, which was closer to a camera when the photo was taken.

Ok, this method is bad, but how to reshape it correctly?

The transformation, which we need, is called homography, and I found a nice post, which explains it. OpenCV even has a function getPerspectiveTransform for it. But part of the challenge was to not use such libraries, so I implemented it myself.

Let me briefly explain the idea. We say that when we take a photo, all points are projected to some plane (by drawing a line between it and a camera, and looking where it intersects the plane). We don’t know the actual camera location, but we want to estimate it based on the fact that we know the positions of specific points (in our case table corners). After that, we can take other pixels from the photo, and calculate their actual physical location.

We can express this transformation as multiplication by some 3x3 matrix with unknown coefficients. One of the coefficients could be explicitly set to 1.0, as we don’t care about the scaling factor. We have 4 corners and for each of them we can write down 2 linear equations (for x and y coordinates). Overall 8 equations and 8 unknown variables, so we can find a unique solution via Gaussian elimination. I skipped some details, but it should be possible to find good explanations about it on the internet.

Correctly reshaped picture (do you see the difference?):

Pieces detection

Great, we reshaped the picture, what is next? We need to separate pieces from the background. Again, there are probably some CV libraries, which can do it out of the box, but we want to do it ourselves.

The worst thing you can do when approaching problems like this is to start writing something smart and complicated. Usually, it will not work, and you will lose a lot of time. As in all other parts of this post, I suggest thinking about how you’d approach such a problem yourself before reading my solution.

As all pieces, I cared about, were white, and the background was dark, I decided if a pixel is part of a piece or not by a simple formula:

fn is_piece_color(color: Color32) -> bool {

color.r() + color.g() + color.b() >= 500

}

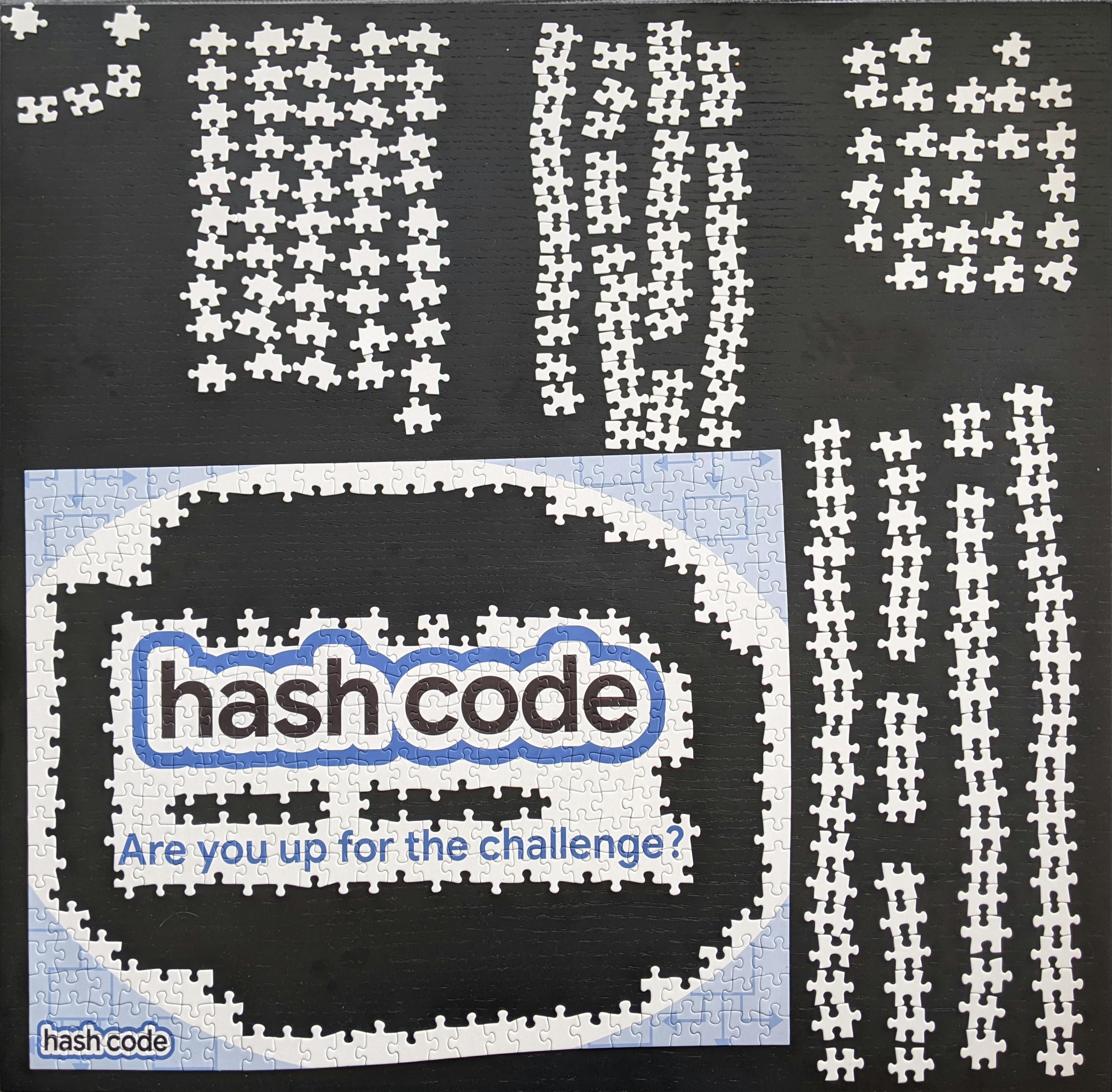

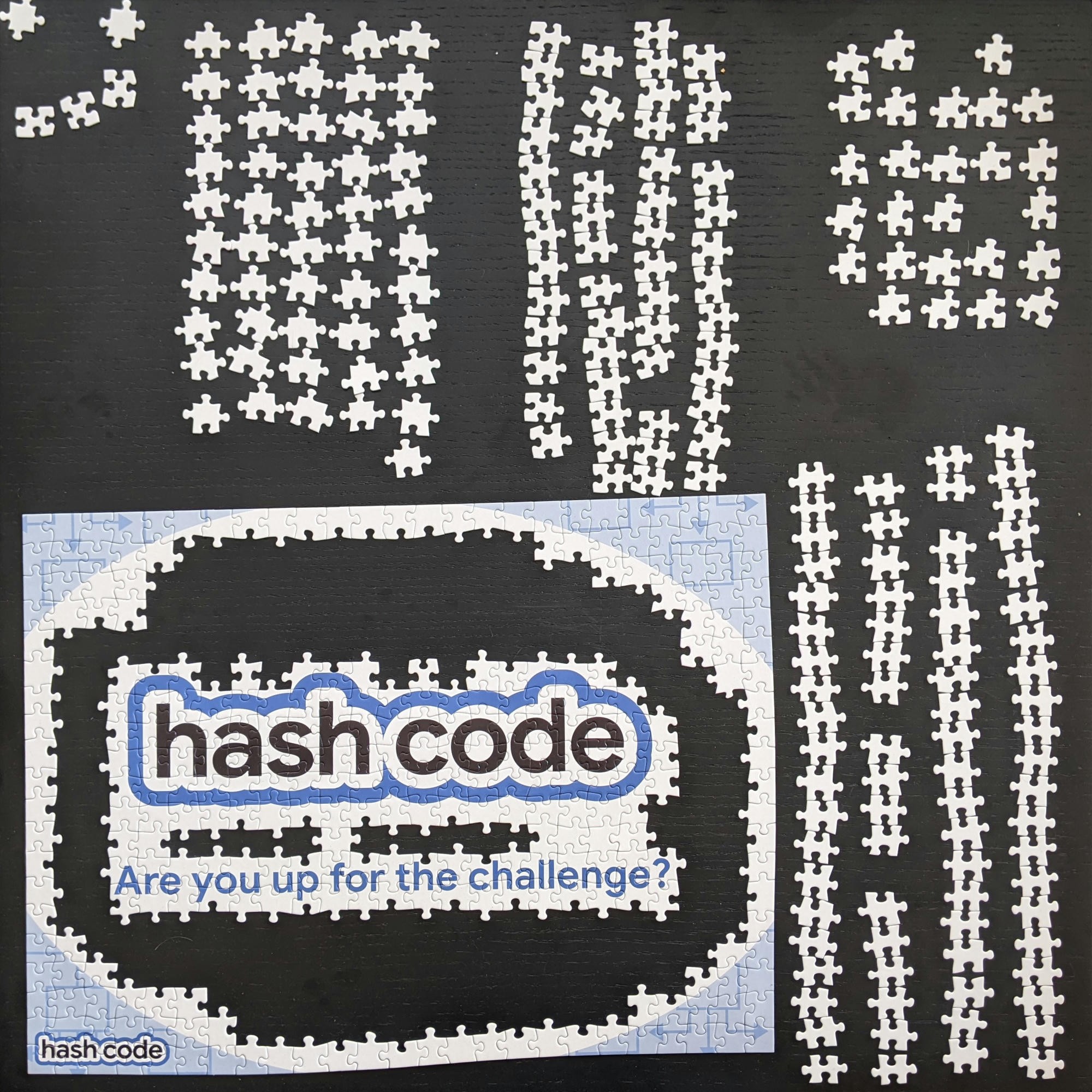

I got this result:

I joined all connected pixels into groups, tweaked a constant a little bit, and got this picture:

Obviously, it is not ideal. Some pieces were merged together and some didn’t contain all the pixels, but it was good enough to start implementing the next stages of the algorithm and test things.

Borders detection

We want to split a set of pixels from one piece into inner points and the border. It is very easy. We say the pixel is on the border if there is another pixel near it, which doesn’t belong to this piece. After implementing this check, I got a picture:

When we know a set of pixels lying on the border, we need to put them in some reasonable order. Intuitively we just want to go around the piece, and write down all the pixels, but in reality, it was hard to come up with some reasonable algorithm, which does it. We need this order to be able to match different pieces together. If we have it, we can traverse two borders at the same time, and check that pixels are not too far from each other.

More formally we want to find such an order of pixels that the distance between each pair of neighboring (in that order) pixels is quite small (e.g. less than 3 pixels). Finding such a permutation for a general graph is NP-hard, but we can somehow use special properties of our graph to simplify the task.

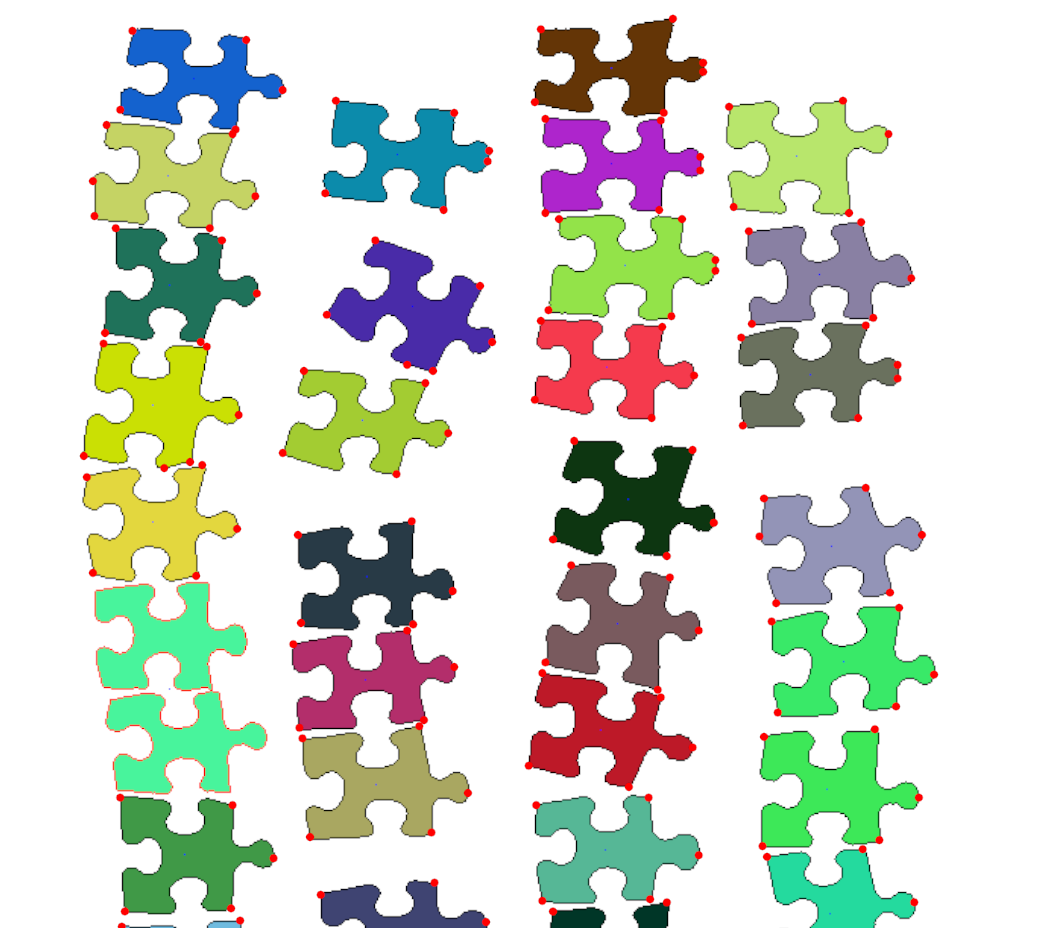

I implemented some greedy algorithm, which just always went to the closest not visited pixel. And then applied some local optimizations to improve generated permutation. Mostly it found good solutions:

But sometimes something didn’t go well:

Again, we don’t need a 100% working solution (at least in the testing stage), we can improve it later if it becomes the bottleneck. Btw, if somebody knows a good algorithm for this task — please let me know :)

Corners detection

Great, we detected a border of a piece, and put all pixels of it in, for example, clockwise order. Now we want to split this border into four parts, where each part corresponds to one side of a piece. I hope intuitively it should be easy to understand what side is, but it is hard (at least for me) to formally define it.

Why do we actually need to detect separate sides?

- First, it makes matching easier. When we try to fit one piece with another, we only need to try 4x4=16 possible ways.

- Second, it makes the later graph task more discrete. For example, we can say that we need to put pieces in a grid, and for each piece choose one of 4 possible rotations. After that, we know which pieces are connected and by which sides.

So, how to detect corners? Again, I encourage you to think about this problem before reading my solution!

How are corners different from other points of the border? One difference is that if you look at several pixels before the corner, and several pixels after, the direction changes a lot. But it is also true for some other points… Also, it is hard to express “changes a lot” in the algorithm. You will probably need to choose some constants like how many pixels to take before and after, and what angle is big enough. And maybe for different pieces, you will need to use different constants.

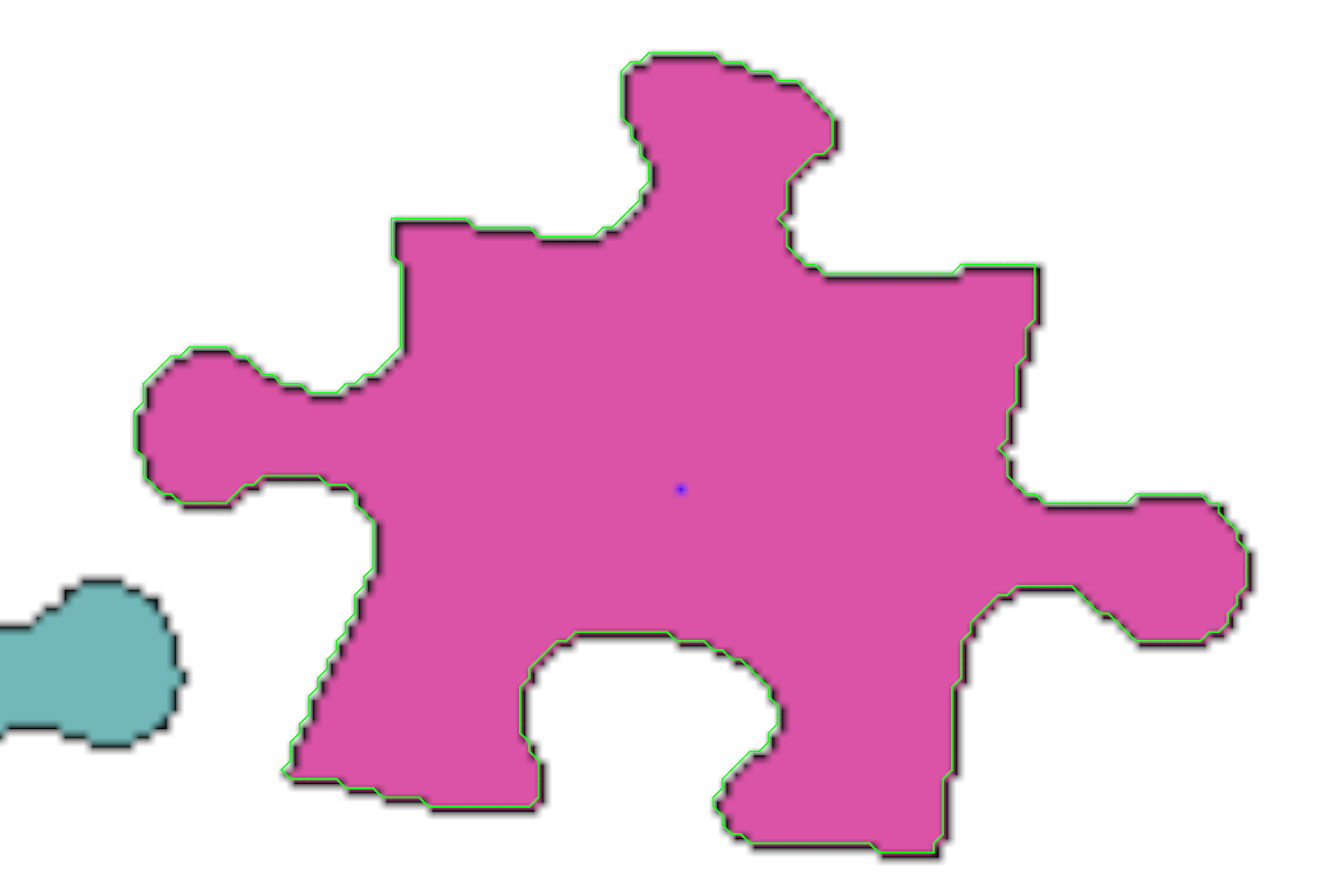

Another algorithm, which I tried worked like this. Let’s first calculate the center mass of the piece (you can actually see the blue dot in the pictures above). Then for each pixel from the border calculate the distance to the center. Then we say the pixel is probably a corner, if it is further from the center, then pixels nearby. It already works pretty well:

This algorithm detects all corners, but also sometimes some additional points (but not too many of them, which is good). We can try to iterate over all possible fours of detected points and choose a four, which is the best by some metric. We only need to come up with a good metric. Intuitively, corners should form a rectangle, so we can choose the most “rectangular” four points. I did two things:

- For every three consecutive points, I calculated the angle between them and compared it with 90 degrees.

- Divided the longest distance between consecutive points by the shortest distance. The idea is to exclude options, where we have two very close points.

Then I multiplied two values and found the minimum score. Probably there are better/easier ways of doing this, but I just played with formulas until they worked well on real examples:

Fitting borders

Okay, as we detected the sides of each piece, now it should be pretty straightforward to say if two pieces fit or not. We just put them nearby, iterate over pixels from both sides at the same time, and check that the i-th pixel from one border is near the i-th pixel of the border of another piece.

Wait, put them nearby? How?

We need to apply some transformation (rotation and shift) to one piece such that the metric we try to improve (sum of distances for corresponding pixels) is the best. How to find such transformation? We can try to fit the corners of one piece with corners from another piece and hope other points will also fit nicely.

There was also a problem connected to the fact that we don’t detect pieces on the photo ideally. The actual border of the piece is not very white on a photo, so we don’t mark it as part of the piece, and our pieces are smaller than in reality. And when we try to fit two pieces, which should fit in real life, borders don’t match exactly. I first tried to fix it by applying an additional shift and saying the corresponding pixels should have a distance similar to this shift:

But it didn’t work very well, because, for some pairs of pieces, which shouldn’t fit at all, I got good scores, because even after the shift, borders intersected much, and the distance between corresponding pixels was negative but equal to the shift by absolute value (and I didn’t come up with a way to distinguish good positive distance and very bad negative, as I only knew the absolute value of it).

A good fix, which helped, was to just enlarge each piece by two pixels, and then try to match borders exactly, without a shift.

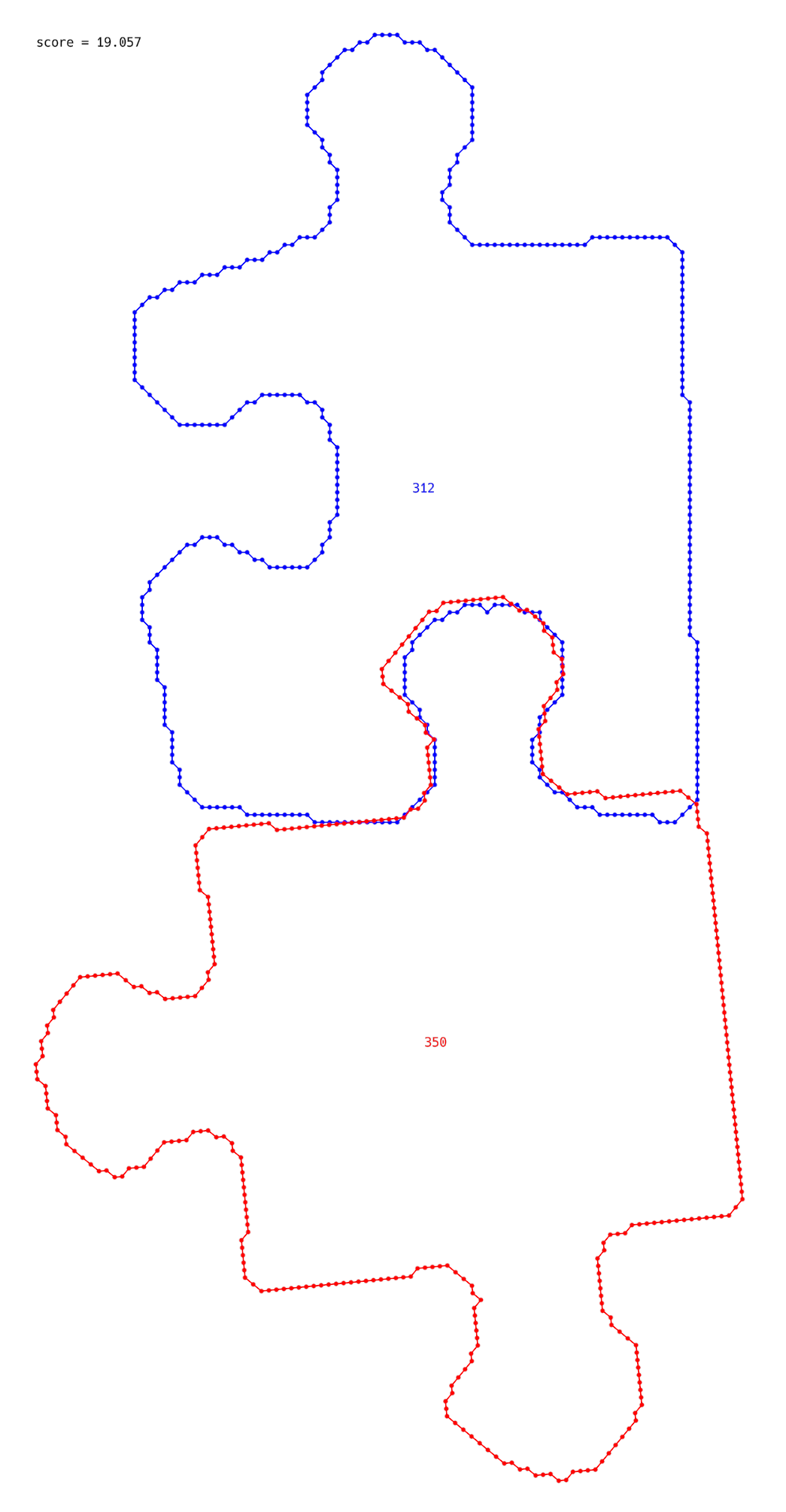

Back to the trick, where we chose needed transformation based on the corners. Sometimes we don’t detect corners precisely (maybe off by a couple of pixels). But when we use a slightly incorrectly detected corner, it changes the transformation quite a bit, and we receive not-so-good results:

Obviously, we can rotate the bottom piece a little bit to fit more nicely, but how to say it to the algorithm?

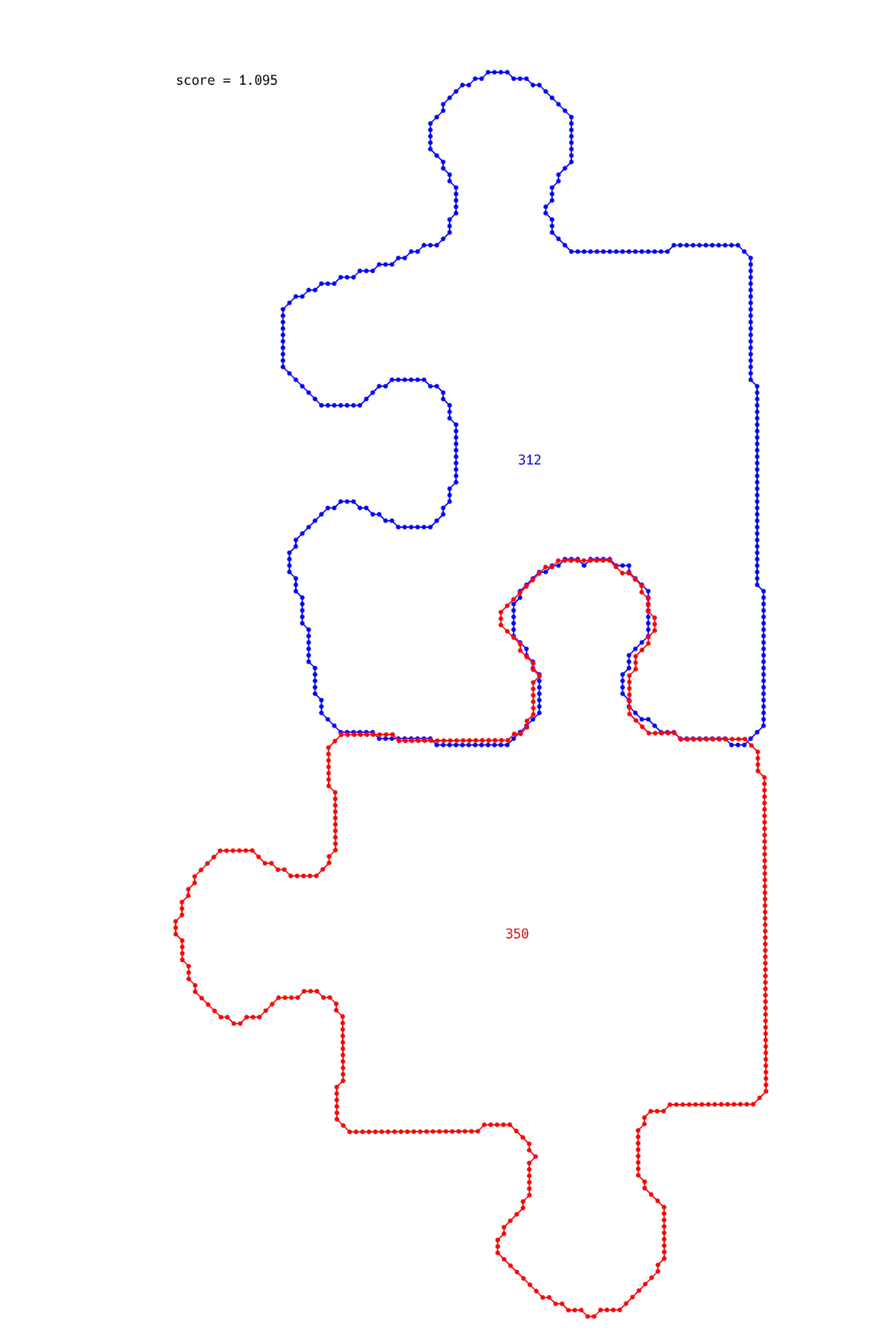

I estimated the transformation by corners first and then tried to change it a little bit with local optimizations. For example, we can calculate the score, shift the piece a little bit in a random direction, and check if the score improved. If not, we shift the piece back, but if it improves, we try to do it again. And we can also try to rotate the piece in the same way. After applying this technique I got a good result:

The last part

Great, we are almost there! Congratulations if you read till this point!

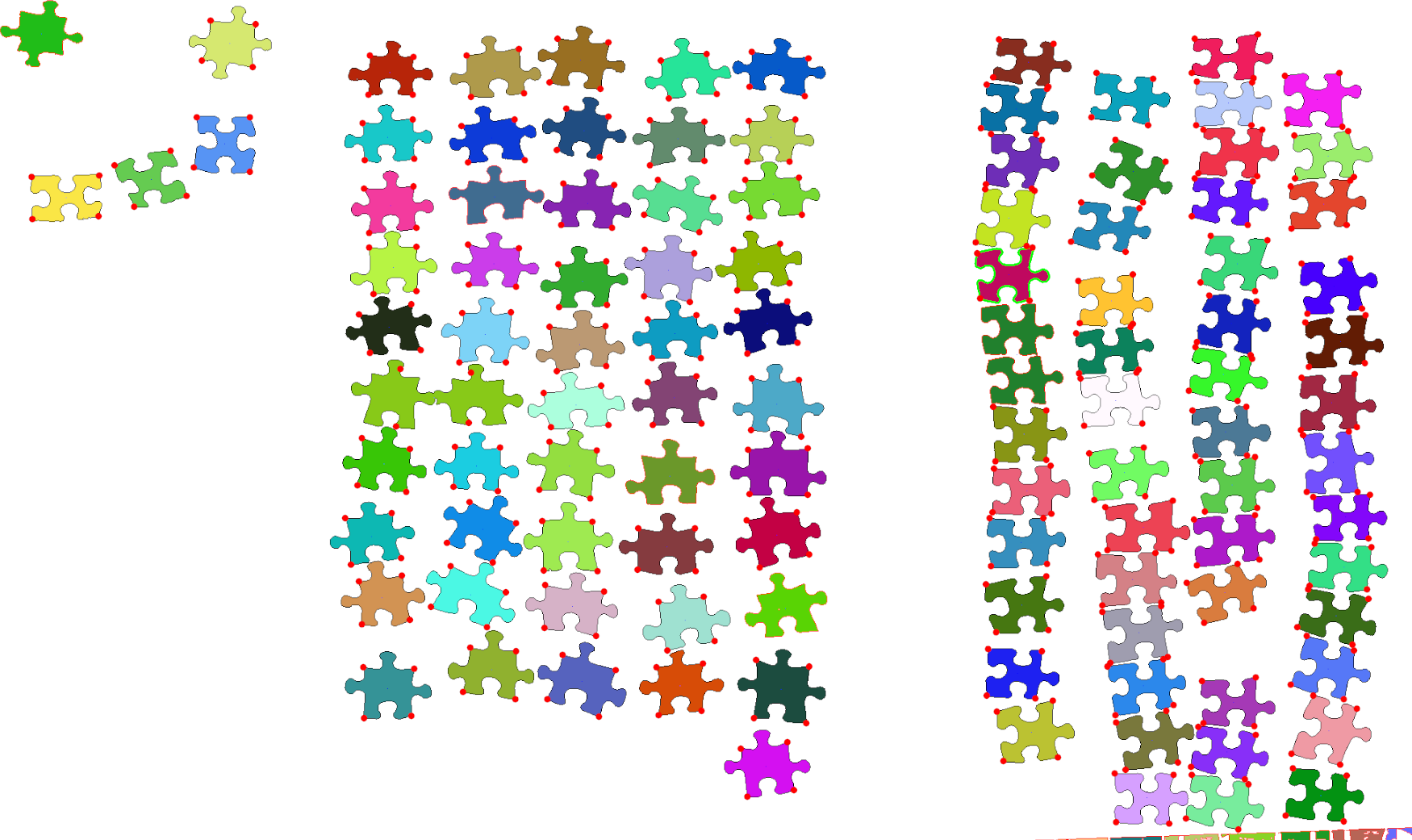

If for each pair of pieces we can calculate how well they fit, we can build a graph on it. And apply some algorithms to it to find the best possible overall fitting. I didn’t know a good algorithm, which solves it perfectly, so I wrote a very easy greedy approach. Just try to fit pieces with the best possible scores, until you connect all of them into one figure.

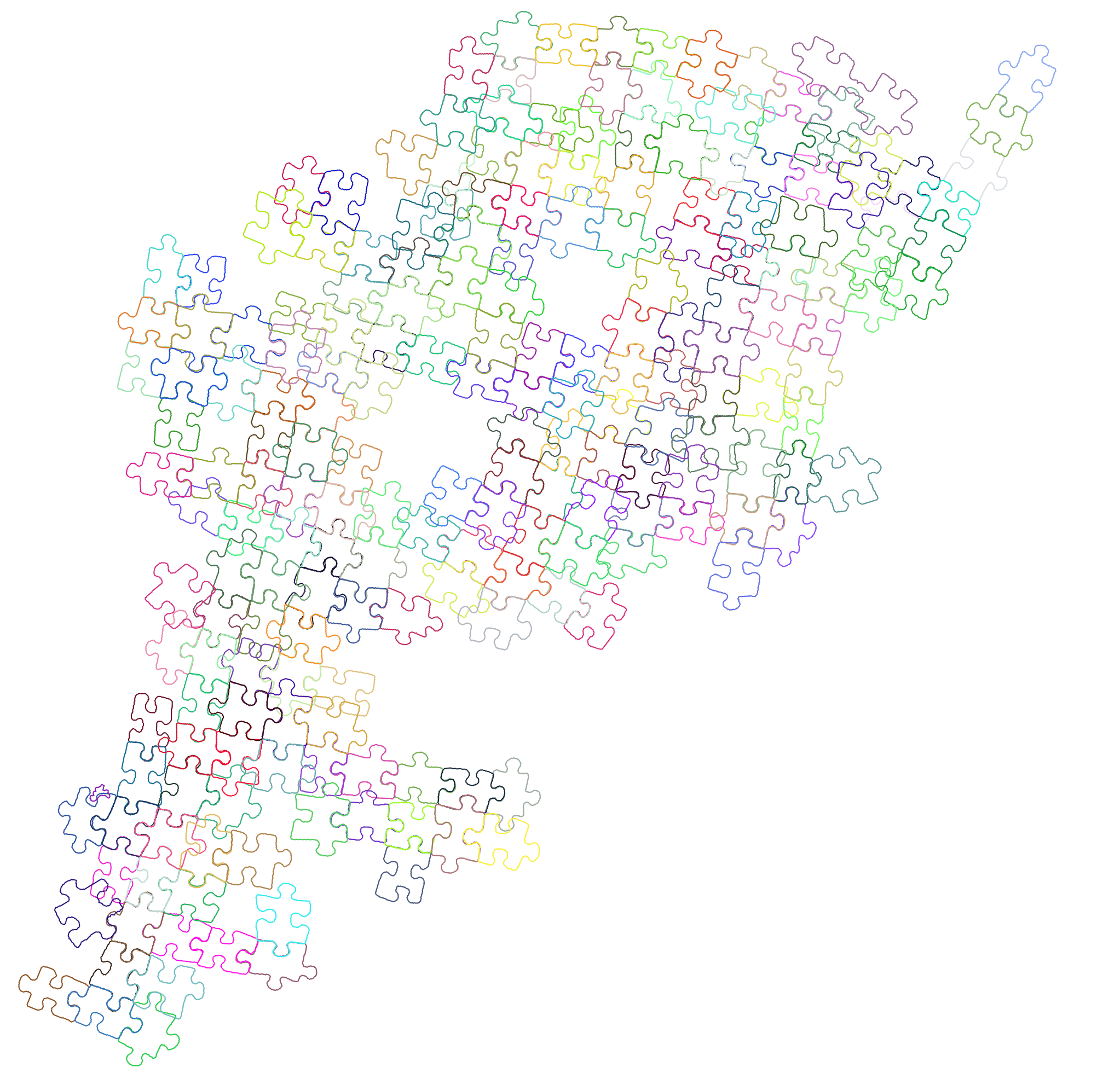

Obviously, it is not perfect, but after all the work done before that moment, I wanted to see some real result, even if it will not give the absolutely correct result. And what do you think I got?

Well, this looks very incorrect! But it also looks a little bit promising. You can see that some pairs of pieces actually fit pretty nicely.

Anyway, this post is already pretty long, and there is a lot more to cover in this story, so I decided to split it into two parts. See you in part 2!

If you want some spoilers, you can check the GitHub repository with the source code and images: https://github.com/BorysMinaiev/jigsaw-puzzle-solver.

If you read till this point and know Russian, consider subscribing to my Telegram channel with similar posts: https://t.me/bminaiev_blog.